By Chidi Anselm Odinkalu

A little under ten years ago, I was exercised by an overwhelming curiosity to understand what made it possible for the Nigerian military to capture the country and how they managed to accomplish that with such seamless adaptability. A friend and former soldier promised to introduce me to someone whom he trusted would meet my needs, if not exceed them. I looked forward to meeting a retired soldier, disheveled journalist, or frumpy researcher.

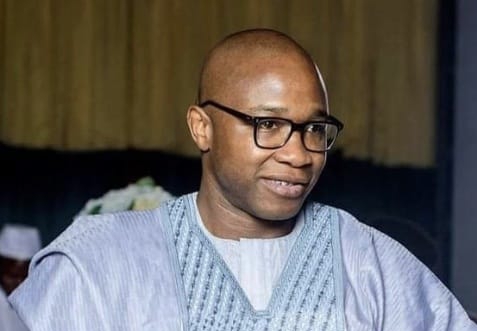

When eventually I met him, Tunde Jonathan Mark, who has died of cancer-related causes at 51, did more than meet my expectations; he blew me away. He showed up at well over six feet in height, a hunk of a man, with no paper or pen, just his head and the total recall buried in it. Our conversations ranged over the minutiae of people, places, putsches, pitchforks; he knew them all and reeled them out with effortless ease. His knowledge of Nigerian military history, politics, and public policy was encyclopaedic. He had one of the brightest minds I ever met.

To ease me into the exploration, Tunde arrived our next conversation with a copy of the Nigerian Defence Academy: A Pioneer Cadet’s Memoir. The author was Paul Osakpamwan Ogbebor, the retired army Colonel who died in 2020, a leading member of the Regular Course One (RC-1) of the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA). Other members of the RC-1 include former second-in-command to Sani Abacha, General Oladipo Diya; former Chief of Army Staff, General Aliyu Mohammed Gusau; his predecessor in that office, General Salihu Ibrahim; former administrator of the Federal Capital Territory, General Mamman Kontangora; and former Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral Allison Madueke. So began our mutual book club.

Over the next few years, Tunde became my teacher about more than just the Nigerian military. His knowledge about the country and the world was peerless and he was very generous with it. He had this sonorous voice; a clarity of mind that testified to his training as a scientist, with the most clipped accent garnished with a sense of humour that dripped with acid. His vocation, it seemed, was to connect the most implausible dots with evidence that was hidden in plain sight.

Tunde Jonathan Mark was born on 13 October, 1971. His father, David, a soldier who would emerge as leader of the NDA’s RC-3, had been commissioned an officer into the Nigerian Civil War which ended at the beginning of the previous year and had just been promoted a Captain. At birth, his father named him after one of his best mates in the RC-3, Tunde Jonathan Ogbeha, who would also go on to become an army General and politician.

Like his father and his father’s best mate after whom he was named, Tunde had it in him to pursue a career in the military. He had the physical presence and aptitude to excel in the martial vocation. Indeed, he began his education at the Military School in Yaba, Lagos. But he had a humaneness about him that abhorred the casual and chronic brutality that came to characterize the Nigerian military and he detested the caricature of a professional force that it evolved into.

For his High School, Tunde attended Bradfield College, the independent preparatory school in Berkshire, England, where he honed the determined humaneness that would shape his worldview. He trained as a scientist in biochemistry and immunology at King’s College, University of London and also obtained a graduate degree Biological Science from the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The son of a father whose life is steeped in the idea of power; Tunde preferred to focus on the power of ideas. His training as a scientist equipped him to be quite clinical about issues. He had an unusual ability to cut to the heart of the most intricate of issues with dispassion and clarity irrespective of who was interested. His father’s peregrinations in the Nigerian Army may have given him opportunities that most other young people of his generation did not have and access to knowledge about the military and the world beyond the reach of most but Tunde happily accepted that privilege with a sense of dutiful responsibility.

Tunde did not just school me in the institutional history of the Nigerian Army and its leaders, he also became my copy editor as I proceeded after our tutorials to undertake research that would eventuate in writing about military rule and its obsession with indispensability. His eye for detail was unsettling and he was unsparing in his rigour. If there was any doubt about any particular claim of fact, Tunde would chase down original evidence to authenticate its veracity or disprove its authenticity.

Tunde was a wizard when it came to finding access to the most rarefied documents and sources but even that skill took second place to his utter mastery of the written word. He brooked no split infinitives or passive tone. He was that rare editor who was expert in your subject matter and knew better than you how to manipulate the written word but made you both comfortable and grateful to have him in your corner.

The illness began innocuously enough. It was shortly before the pandemic and a dental complaint had defied the most persistent attentions of excellent dentists, who asked for a second opinion. On a routine trip outside the country, Tunde visited dentists who took screens. Further investigation followed and then came the news that there were malignant lesions in the mouth reaching into the jaw. An infinite number of hospital appointments were to be followed, first by surgery and then the ordeal of chemotherapy during the pandemic.

The malignancy was aggressive but so was Tunde’s optimism. He never doubted that he would beat it. Even after the doctors pronounced the malignancy as untreatable, Tunde retained good humour, always keeping focused on the big issues until the end. Not even the added complication of having to deal with the coincidence of chemotherapy and a COVID-19 infection at the same time could dampen either. He beat the COVID.

Tunde could be withering with word economy. As ill-fated United Kingdom Prime Minister, Liz Truss, prepared for her coronation last August as leader of the Tory Party, Tunde delivered his verdict in five words: “what a waste of cardboard….!” In response to a Nigerian governor who took to a weekly habit of releasing singles after losing presidential primaries, he asked: “who is this hirsute gremlin of a man, bawling like a sailor everywhere?” Reconciled like the scientist he was to the reality of his own earthly mortality, his verdict on his own ordeal through prolonged cancer treatment was: “quite an adventure.” Despite the ravages of the illness, he insisted “….I can’t complain.”

As his health waned at the beginning of October, Tunde was worried about the impact of the pandemic on healthcare provisioning worldwide and on the absence of a capable health system in Nigeria. His abiding ambition was “to ghost write an insider’s account of this administration,” he said, whooping that it would be “super cool!”

As recently as the last week of his earthly sojourn, Tunde looked forward to returning to Nigeria to experience the preparations towards the 2023 elections but, even as he desired it, his condition deteriorated and he had to return to hospital. In the end, the Grim Reaper could not be assuaged and Providence had better plans.

In a fitting coda to his life, Tunde passed away in the early hours of African Human Rights Day on 21 October, 2022, eight days after he turned 51. The release announcing his death was issued under the heading: “Senator David Mark Loses Son to Cancer.” Uncompromisingly proud of his roots and grateful for them, Tunde Mark was more than his father’s son. He was his own man. He is survived by his wife and their young daughter.

A lawyer and a teacher, Odinkalu can be reached at chidi.odinkalu@tufts.edu