By Edwin Madunagu

Readers are referred to a short piece I wrote as my own contribution to the prefatory note for a 2021 “Book of Honour” done for me by the Nigerian Left, “Edwin Madunagu at 75: Tributes and Reflections.” The book was edited by Comrade Chido Onumah. This tribute to Comrade Seinde Arigbede who died early this month, November 2022 “dovetails” with the prefatory notes.

Forty-six years ago, as I turned 30, I left Lagos for Ibadan. From Ibadan, together with a comrade of the same age (Comrade BJ), I left for a rural community somewhere between Gbongan and Ile-Ife in present-day Osun State. There we joined others, similarly inspired like us, about ten in number, male and female, excluding a kid (Timi) and a baby (Irawo) whom we took turns to care for in order to free their mother (Comrade Dunni Arigbede) to participate fully in revolutionary duties.

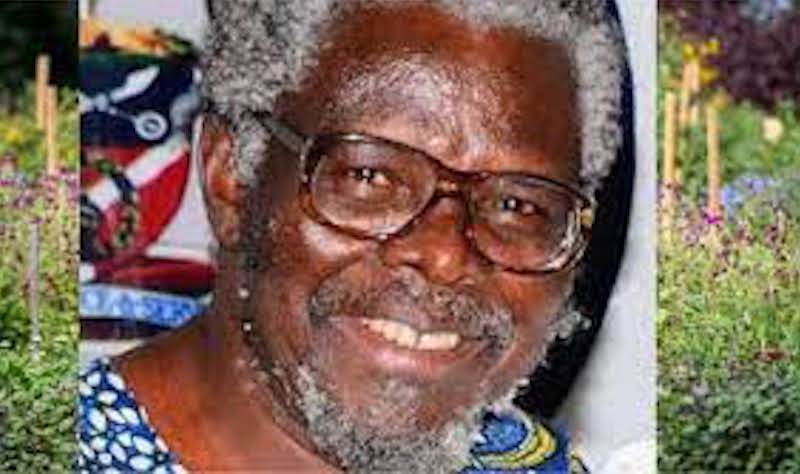

The house where we converged was “tenanted” by a revolutionary couple, Comrade Seinde Arigbede (husband) and Comrade Dunni Arigbede (wife). They became, in effect, our “hosts” and essentially “coordinated” us at the beginning. As days rolled by, this “coordination” was no longer necessary. Comrade Seinde was very versatile, talented, creative, physically very strong, brilliant, humane and humanistic. Comrade Dunni was an able “conscientiser” in Yoruba and English and was also, in my assessment, the most confident “mission driver” of the group: able to maintain a speed of 120 km/hr in face of danger. I stooped to learn various things from them all: Seinde Arigbede, Biodun Jeyifo (BJ), Gbolaga Akintunde, Dunni Arigbede, Tony Engurube, Bene Madunagu, the Arigbede twins: Taye and Kehinde, etc.

We assembled to inaugurate an underground Marxist revolutionary vanguard, an “external” vanguard, embedded in the peasantry. While some members including Comrades Dunni, Seinde, Gbolaga and the Twins were fully in residence, others were not. Of these “others,” some were partially in residence (Comrade BJ) while the rest (including Comrade Tony and Comrade Bene) were “visiting” members. The non-resident members were, however, continually in touch with the Headquarters, or HQ. I was not only fully in residence, I virtually disappeared from the outside world for between 9 and 12 months. Let us call the group the Revolutionary Movement for the Liberation of Nigeria (REMLON), and its mission the “Extraordinary Expedition” (EE).

The strategic objective of the “Extraordinary Expedition” (EE) was to inaugurate an armed struggle in a socialist revolution which we recognized had been going on at a certain level in our country, Nigeria. The armed struggle did not happen. But it almost did. And in an attempt to force it to begin, we also almost ended up in self-liquidation. However, despite our failure to inaugurate an armed struggle, we succeeded in transforming ourselves into authentic revolutionaries.

It was when I was leaving the Headquarters after the collapse of the expedition that our peasant comrades knew, through my contact address and full name, that not only was I not an Ijesha man, but that I was not even of Yoruba parentage. For I had integrated completely with them and had been one of their conscientisation discussion leaders in the Yoruba language for at least the preceding six months. The scene of separation was so emotional.

The Extraordinary Expedition had profound effects on all the participants. But, as expected, the effects were of different kinds on different comrades, with some differences from the average less significant than others. It was this variation in differences that made it possible for Biodun Jeyifo (BJ) and I, then Bene, to regroup almost immediately after the collapse of the expedition.

We tried, in Extraordinary Expedition (EE), to transform ourselves from mere revolutionary intellectuals to proletarian revolutionaries that could indicate or chart a new line in the revolutionary socialist transformation of Nigeria. We tried to create a revolutionary agency that was knowledgeable about Nigeria and Nigerians, credible and essentially different before the working peoples and rural masses of Nigeria, an unalienated and non-exploiting revolutionary agency. We tried to deepen a rejection and banishment of what we regarded as illusory peaceful road to socialist transformation, and to “conscientise” the rural population to do the same.

We tried to deepen in our consciousness the maxim that genuine liberation was the task of the people themselves. But revolutionary intellectuals who desired to take part in this project must find their roles in the Communist Manifesto, domesticated. We tried, in summary, to create a new type of revolutionaries, a new agency, a new family. We tried to banish discrimination against, and oppression of women.

We tried to raise the concept and practice of “revolutionary collectivity” and “gender equality” to new levels – banishing patriarchy along the way. We kept, maintained, secured our home, HQ, cultivated a large part of what we ate, cooked and fed collectively. We took turns to care for the kids, feeding and cleaning them. We farmed, kept a rabbitry, diverted a branch of a nearby stream into our fenced compound and rediverted it out.

From the HQ we tried to expand our reach and base towards Ede and beyond, to Ogbomosho and met “them.” In another direction, we extended to Ifetedo and Okeigbo. In Ede we tried to build a second headquarters, HQ2 – with our own hands, but excluding the physical involvement of the peasant members of the group. This “expansion and extension” proceeded simultaneously with the efforts to establish ourselves in the localities and neigbourhoods of each and every member of the peasant sub-group. In executing our programmes, projects and missions we tried the Leninist principle of “committee work” and discovering, strengthening and employing “compatibility” in the selection of committees and sub-committees.

The Extraordinary Expedition lasted approximately 12 months: Mid-1976 to Mid-1977. When Comrade Bene who had been to the HQ less than a month earlier saw me suddenly in Calabar she knew that “something” had happened. But for several hours I was unable to say anything. She left me severely alone. Readers can guess when finally I was able to “open up.”

I met Comrades Dunni and Seinde Arigbede again a decade later, in 1987, when they came to see me at The Guardian, in Lagos, after my “pull-out” from the “Political Bureau.” They came to express their “revolutionary solidarity.” Just under 30 years later, in January 2016, Comrade Bene and I met the comrade-couple at the same HQ, Ode-Omu where I had left them almost 40 years earlier. This last meeting took place after the “BJ at 70” Conference at the OAU, Ile-Ife which we all – BJ, Seinde, Dunni, Bene and I – now aging and ailing, had attended from our different stations. The approach to the old HQ had changed so much; so had the host-community, Ode-Omu. Hence, Comrade Bene and I needed the assistance of Comrade Wumi Raji of OAU to locate it. But the HQ itself and the structures within it had remained almost unchanged or had remained “invariant,” as they say in Mathematics.

Comrade Seinde Arigbede died early this month, as we noted at the beginning of this tribute.

Comrade Seinde Arigbede, a Revolutionary Salute!!

Edwin Madunagu, mathematician and journalist writes from Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria.