By C. Don Adinuba

There is so much the Igbo can celebrate about themselves. Take their brilliant performance in education which is phenomenal. Whether in the West African School Certificate examination or the Joint Admissions Matriculation examination or the entrance examination into Federal Government Colleges or into the Federal Government-owned School for the Gifted and Talented in Abuja, the story is the same. Even in global educational competitions, the Igbo are outstanding.

This is by no means fortuitous. By 1945 when the Second World War ended, there were a handful of Igbo graduates because the Igbo live in the interior; the Europeans who brought education to Nigeria came through the seas. Yet, within 20 years the people had begun to compete effectively with the Yoruba who had a historical advantage of over half a century over them in terms of higher education; the Yoruba have towns like Badagry and Lagos which are on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean. By 1965, the Igbo had, as Chinua Achebe puts it in The Trouble With Nigeria, “wiped out their educational handicap in one fantastic burst of energy.” The famous nine Argonauts like Okechukwu Ikejiani, K. O. Mbadiwe, Mbonu Ojike, Okwunodu Okongwu, and JBC Okala, whom the Great Zik of Africa sent to the United States “in search of the Golden Fleece,” played a significant part in this social revolution.

As Nigeria was gaining independence from British rule in 1960, Nnamdi Azikiwe, the American-educated Eastern Nigerian premier, was giving the nation its first autonomous university in the little-known town of Nsukka. The Igbo State Union was firing on all cylinders in its campaign for the spread and deepening of education throughout the Igbo territory. Igbo towns and villages were competing among themselves for the establishment of schools and were also raising funds to send promising but financially handicapped youth overseas to study. Meanwhile, the Christian missionaries in Igboland engaged in a healthy competition in their establishment and management of schools. No wonder, the first Nigerian University of Ibadan vice chancellor, Kenneth Dike, was Igbo, just as the first University of Lagos vice chancellor, Eni Njoku.

As adumbrated above, there are quite a number of other fields where the Igbo have excelled. Trading, manufacturing, innovation, technology, and the professions easily come to mind. Most Nigerians may not know that there are more Senior Advocates of Nigeria (SANs) from Anambra than from any other state. For a people who lost a 30-month Civil War between 1967 and 1970—with all the consequences—the achievements of the Igbo are truly phenomenal.

However, rather than celebrate these attainments, the Igbo elite have over the recent decades been wont to refer to a glass of water as “half empty” instead of “half full.” Ohanaeze Ndigbo, frequently referred to in the public space as the apex Igbo socio-cultural organisation, has been celebrating the annual Igbo Day on September 29. Alex Ogbonnia, the Ohanaeze publicity secretary, has in a statement announcing the celebration of this year’s event in Enugu, spent considerable time chronicling the Igbo tragedies which, according to him, culminated in the massacre of 30,000 Igbo people in Northern towns and villages on September 29, 1966. Hence, the choice of September 29 as Igbo Day.

Why not on a day associated with a great positive development? The American people and government honour African Americans with a national public holiday on June 19 in commemoration of slavery abolition in Texas in 1865, and another federal holiday on the third Monday of January in remembrance of Martin Luther King who was born on Monday, January 15, 1929. It is the primary responsibility of the leadership in every organisation, family, kindred group, town, city, or nation to radiate optimism and produce positive energy. Conversely, leaders who stress the negative end up creating a toxic environment. They breed generations of angry followers who whine and sulk endlessly.

According to Western researchers, al-Queda, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and other terrorist organisations operating in the name of Islam are driven by hate and mind poisoning created by mullahs in madrassas who always bemoan in their sermons the “loss of the Glorious Islamic Era” during which Spain was conquered by the Moors, only to be driven away by the Crusaders after several centuries. The young men grow up with a terrible sense of vengeance against the West, thus their easy embrace of violent ideas.

Biafran groups didn’t grow overnight. They have their roots in the sing-song of Igbo marginalisation and similar acts. Historians speak of remote causes, and not just the immediate, when certain things occur. Driving from Asaba into Onitsha, the first thing to arrest your attention is the huge statute of Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, and a few kilometres away is a similar statute in Nkpor, Idemili North Local Government Area. These are not statutes of Ojukwu returning from Cote d’Ivoire in 1981 or of a young Oxford graduate in the 1950s, but those of a fighter in military fatigue, complete with a rifle strapped to his back, in 1968.

Ojukwu ironically did not crave the reputation of a perpetual fighter or a congenital rebel. He rather cherished the image of a nationalist, reminding the public at every moment that he left the public service of the Eastern Nigerian Region for the Nigerian Army because as independence was approaching in the 1950s he saw the country becoming more regionalised rather than more united. The war, he argued repeatedly, was forced on him by the nasty events of the late 1960s. He told the defunct African Guardian weekly in a major interview in 1986 conducted by Ted Iwere and Okey Ndibe that he “will fight again if Nigeria’s sovereignty or unity is threatened.” As evidence of his nationalist streak, he did not join the Igbo-dominated Nigerian Peoples Party (NPP) in 1982 following his return from exile, but the National Party of Nigeria (NPN), the Northern-dominated government party that granted him amnesty. He explained he joined the NPN to bring “NdIgbo back into the Nigerian mainstream.” As years went on, he did not join any of the parties favoured by the Igbo elite like the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) in the Fourth Republic but chose the All Peoples Party (APP). His joining the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) in his later years was something like an outlier.

As another Igbo Day approaches, it is crucial to let those who think they are being realistic by stressing the tragic in Igbo history that they are in error. Francis Fukuyama observes in The End of History and The Last Man that negative-minded persons are often considered realistic and profound even when events prove them wrong, but optimists are regarded as naïve even when history validates their position.

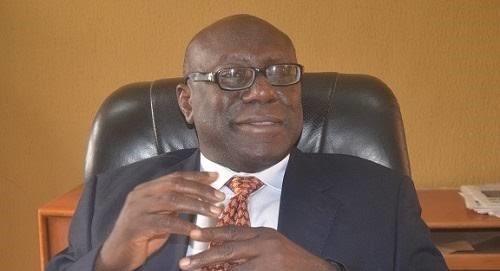

Emmanuel Iwuanyanwu, the new Ohanaeze leader, appears to have his head screwed in the right place, to borrow a peculiarly American expression. He is in a position to lead the Igbo on a charm offensive, to embrace what Harvard preeminent political scientist Joseph Nye has identified as soft power, that is, the battle for the hearts and minds of the world. Soft power, and not hard power represented by America’s immense nuclear power and military interventions in Vietnam and elsewhere, is responsible for Pax Americana, the foremost consequence of the United States’ triumph over the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Soft power makes others want to imitate or behave like you, frequently unconsciously. It is about mind management. This is the Igbo challenge.

Adinuba is a former Commissioner for Information & Public Enlightenment in Anambra State.