By Uzor Maxim Uzoatu

I am in tears as I write the words here.

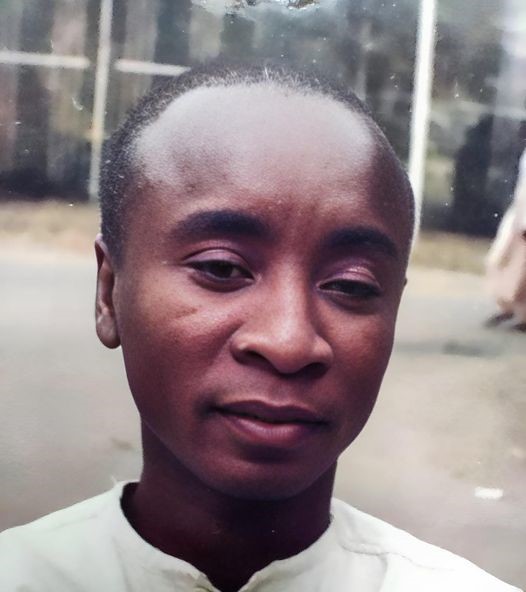

It has been shattering for me on hearing of the passing away of my ever rendering soulmate Pita Okute whose original name is Iheanyi Iwuofor.

As things stand, it would be killing for me to write about Pita Okute in the past tense.

Pita Okute distinguished himself in life as an insightful journalist, an award-winning novelist, and a sublime poet.

Tears flow freely when I re-read his poem dedicated to me – “I Am A Lie (For Borojah, perchance a bigger lie.)”

I have had to go back repeatedly to read the masterpiece of column writing by Pita Okute entitled “Me & My Bottle.”

Pita Okute was so self-effacing that not many Nigerians knew of the many feats he made in his chequered life.

Nigerian literature scored a major high with Pita Okute winning the internationally coveted Tuscany Prize for Catholic Fiction in 2012.

Pita Okute’s masterful novel Wild Spirits beat the competition from many authors out of the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Latin America.

By that great accomplishment, Pita Okute was poised to join the esteemed realm of such revered Catholic writers as Flannery O’Connor, Graham Greene, J.R.R. Tolkien, G.K. Chesterton and many others whose writings reflect the thoughts of the great poet Gerard Manley Hopkins: “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.”

Tuscany Press put forward Catholic fiction as stories infused with the presence of God and faith — subtly, symbolically or deliberately.

Back then, the publicists of Tuscany Press wrote: “We are pleased to announce the novel winner for the 2012 Tuscany Prize for Catholic Fiction: Wild Spirits by Pita Okute.”

According to the publishers, Tuscany Press: “This powerful story takes place in civil-war-torn and religion-torn Africa.

“According to Mr. Okute, the book tells ‘the living story of everyday people confronting the terror and tragedy of civil war with hope and courage.’

“Two priests, a group of nuns, rebels, army soldiers, civilians, and aid workers struggle to maintain their humanity amid the lack of humanity that war inspires in so many.

“Self-discovery comes even to an elderly priest who has seen so much despair; a younger priest must deal with the intense guilt of action in his violent world; nuns must cope with retaining their steadfast faith after being attacked and raped; and army soldiers, rebels, and civilians must variously come to terms with death, injury, and moving on in their world.

“Mr. Okute, a journalist, poet, and accomplished writer in his home country of Nigeria, was born in and continues to live in a part of the world few of us know, but an important country that even now experiences dramatic civil and religious war.

“All those readers who experience Wild Spirits will come away with greater awareness, stronger faith, a greater appreciation for peace, and a determination to practice their faith no matter what may come.”

Now this: After Tuscany Press had praised the novel and given the award, the editors tried to tamper with the manuscript in a manner that Pita Okute did not agree with.

There was a stalemate as Pita Okute who had the courage of his conviction refused to allow his novel to be twisted toward Eurocentric and neo-American evangelism.

Pita Okute did not agree to be published for the sake of it, unlike some other African writers who would forever kowtow to Euro-modernist tendencies.

The novel, Wild Spirits, ended up not being released by Tuscany Press.

It remains a truism that the atrocities of war can be a drawback to writers because of the emotional overload usually at play in the circumstances.

In Wild Spirits, Pita Okute achieves a commendable measure of artistic distance and integrity through his softness of touch.

There is no doubt that at issue in the novel is the Nigeria-Biafra war of 1967-70, but the writer leaves the country unnamed and the characters are a welcome mix of rounded types.

The immersion into Catholicism is not done in a proselytizing manner.

The raping of the Reverend Sister is rendered without squeamishness, especially as her suicidal binge is well-judged in my opinion.

The novel reads like an extended version of the domain of the Russian short story master Anton Chekhov in which ordinary people live humdrum lives that paradoxically underscore the essence of society.

Wild Spirits is sumptuously well-written, and it deservedly won the 2012 Tuscany Prize for Catholic Fiction in a strong field of world-class writers across the globe.

In life, Pita Okute had a distinguished career in Nigerian journalism, particularly in Vanguard newspaper where he criticised Ken Saro-Wiwa’s novel in rotten English Sozaboy for having a “silly plot”.

The criticism so rocked Ken Saro-Wiwa that he wrote Pita Okute into his then novel-in-progress Prisoners of Jebs as Pita Dumbrok, a character that forever kept muttering “silly plot”.

Ken Saro-Wiwa went a step further by writing another novel, the eponymous Pita Dumbrok’s Prison based on the Pita Okute inspiration.

Ken Saro-Wiwa and Pita Okute ended up becoming great friends until the Ogoni leader’s judicial murder by General Sani Abacha.

Pita Okute was my deputy when I was appointed the Editor of the Lagos-based Society Magazine.

I had a hot disagreement with the publisher and immediately offered my resignation.

As I was about to walk out of the door, Pita Okute halted me with these words: “Yo, wait for me because I have also resigned.”

Both of us walked into the lift from the 13th floor office of the magazine, descended and drank beer with the last money in our pockets in Mubo’s shop in the bungalow opposite the office building.

Pita Okute would later serve as the Editor of Mister Magazine, published by Richard Mofe-Damijo, with my younger brother, Isidore Emeka Uzoatu, being his deputy!

They no longer make them like Pita Okute.

My tears…