Our Reporter, New York

Distinguished British-Nigerian historian, Max Siollun, has described the ongoing efforts by the National Assembly to amend the 1999 Constitution and create new states as an exercise doomed to fail.

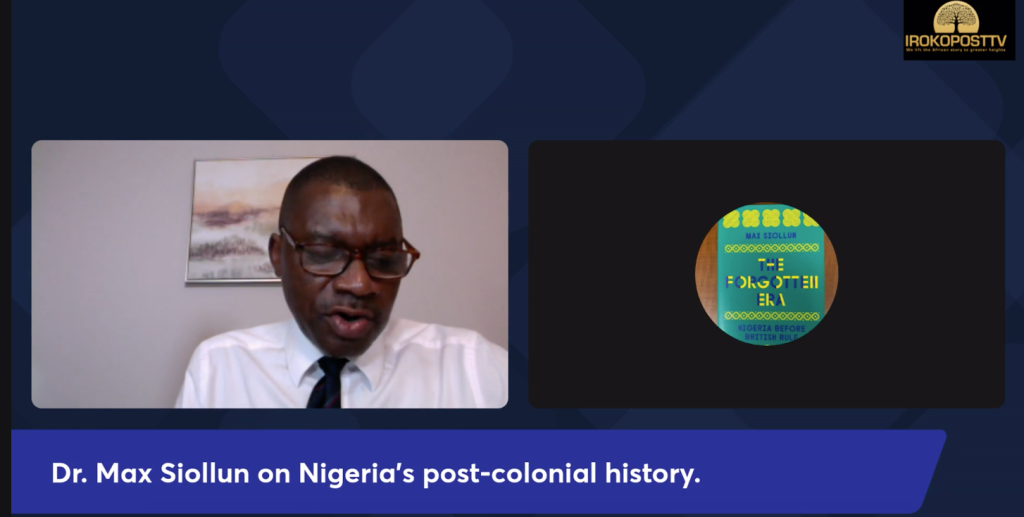

In an exclusive interview with Rudolf Okonkwo on 90MinutesAfrica, the internationally acclaimed expert on Nigeria’s military and political history argued that what Nigeria needs is neither more states nor a new constitution, but rather a new kind of “national reorientation.”

Siollun, author of several bestselling historical analyses of Nigeria’s political and military trajectory, explained that many of Nigeria’s existing states are economically unviable and would naturally resist any move to create new ones, as doing so would reduce their share of federal allocations.

“State creation won’t succeed today because if a new state is created, it will automatically have a right to federal funding, which in turn reduces the allocations to other existing states,” he said.

“The existing states are not going to approve the creation of new states that directly conflict with their own interest.”

He further argued that state creation in one region would inevitably trigger similar demands from other parts of the country, leading to a proliferation of non-viable entities.

“If a state is created in one part of the country, all the other parts will also demand states. So they’ll end up creating so many states that are unviable,” he said.

“State creation is not the solution to Nigeria’s problems, and neither is a new constitution a magic silver bullet. What Nigeria really needs is a different kind of national reorientation.”

On the issue of the country’s worsening insecurity, Dr. Siollun noted that despite the differences in ideology or region—whether it’s Islamic insurgency in the Northeast, banditry in the Northwest, or secessionist agitations in the Southeast—the common denominator is the demographic profile of the perpetrators: disenfranchised young men who feel failed by society.

According to the author of Oil, Politics and Violence: Nigeria’s Military Coup Culture, Nigeria’s insecurity is deeply rooted in its demographic realities, with a large majority of its population under the age of thirty.

“One of the good policies that past governments implemented is the Universal Basic Education (UBE) policy. As a result, a tremendous number of children went through primary and secondary school,” he said.

“However, once they completed basic education, there was no plan to absorb them into the university system or to provide employment opportunities. They had high expectations of social and economic mobility due to their education, but those expectations were unmet.”

He added that the lack of employment and upward mobility for this generation has led to widespread frustration and restlessness.

“There wasn’t a plan for how to provide jobs for these young people. So, it is this bulge of unemployed youths that is giving rise to the security challenges,” Siollun said.

“Until Nigeria develops a youth-focused plan to keep this young, educated but restless—and in some cases, near mutinous—generation gainfully employed, I think the security challenges are going to continue.”

Siollun also addressed the politics of oil in Nigeria, noting that despite growing national tensions, there remains a strong consensus—especially in regions that benefit from oil revenue—that the country should stay together. He emphasized the centrality of oil in Nigeria’s national cohesion.

“Oil is the glue holding Nigeria together,” he insisted. “However, when the oil runs out in the future, Nigeria will have to find a new glue—and a new rationalization for the country’s existence.”