Ikenga Editorial

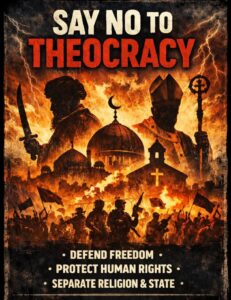

Woro’s massacre underscores a sobering reality. Terrorism in Nigeria is not merely a security problem but a philosophical one. The ideology that sanctifies the merger of religion and state is incompatible with a multi ethnic, multi religious and culturally pluralistic world. A modern nation cannot endure if one segment insists that divine mandate supersedes constitutional consensus. The fight against terror must therefore be multi-pronged. Military vigilance, intelligence reform, border control, economic development and above all ideological counteroffensive are all essential.

In Woro, a quiet agrarian settlement located in Kaiama Local Government Area of Kwara State, the earth is still wet with blood. More than 170 Nigerians were reportedly slaughtered in a single orgy of violence earlier this month. The terror cell, an affiliate of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and known locally as Mamuda did not descend upon the community as marauders announcing conquest; they came under the guise of religious outreach.

A letter had been sent in advance informing the village that they would be arriving to “preach.” Suspicion stirred in the mind of the village head, who alerted the authorities. That act of civic responsibility sealed the community’s fate. What followed was not proselytization but annihilation. Men, women and children were cut down. Bodies were mutilated with a cruelty so methodical that the resulting images seemed less real than nightmarish hallucinations. Weeks earlier, the same network had reportedly unleashed comparable savagery across the Niger State flank of Borgu.

Woro is not merely a crime scene; it is a warning. The massacre forces us to confront a truth too often diluted by euphemism. Nigeria is not simply battling banditry or generic criminality. It is contending with a violent ideological current whose genealogy stretches far beyond our borders. To understand the present, one must trace the arc of political Islam and its global ascent, for the insurgent who raises a machete in Woro often draws intellectual sustenance from ideas born in distant theatres of history.

The contemporary rise of political Islam cannot be disentangled from the trauma of the Six-Day War. In June 1967, Isreal inflicted a crushing and humiliating defeat upon Arab states led by Egypt, Syria and Jordan. The rout was swift and devastating. Air forces were obliterated. Armies disintegrated. Territories fell in a matter of days. Yet the battlefield loss, grave as it was, paled beside the psychological collapse it precipitated. For years, secular Arab nationalism had promised redemption through unity, modernization and socialist transformation. Figures such as Gamal Abdel Nasser as had cast religion as culturally central but politically subordinate to the nationalist state. The future, it was said, belonged to rational planning, not clerical revival.

The defeat shattered that confidence. It was not interpreted merely as military miscalculation but as civilizational humiliation. In the ensuing search for meaning, a theological explanation gained traction. The Arabs had lost because they had abandoned divine law. Secular nationalism, socialism and Western imitation were recast as apostasy. The battlefield had become a tribunal of heaven. Whether this interpretation was historically persuasive mattered less than its emotional potency. In societies deeply anchored in faith, the idea that moral deviation invites divine chastisement resonated powerfully.

Into that ideological vacuum stepped movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood, long suppressed but newly vindicated in the eyes of many. Their thesis was uncompromising. Islam is not merely a personal creed but a totalizing system encompassing governance, jurisprudence, economics and social order. Sovereignty, they argued, resides not in popular will but in divine command. The state must therefore be an instrument of religious truth.

Political Islam is neither monolithic nor uniformly violent. It spans a spectrum from electoral participation to militant insurgency. Yet at its philosophical core lies a tension with secular constitutionalism. In pluralistic societies, the state must mediate among competing convictions without privileging one metaphysical doctrine above all others. When governance is sacralized, compromise becomes capitulation, dissent becomes impiety and political opposition becomes heresy. In such soil, extremism finds nourishment. It is within this ideological landscape that movements such Al-Qaeda and ISIS emerged, transmuting political grievance into sacred violence.

Nigeria’s tragedy is that these currents have found local expression. The rise of Boko Haram, however, cannot be reduced to theology alone. Endemic poverty, corruption, porous borders and governance deficits provide indispensable context. Yet its animating creed, its rejection of secular education and constitutional order, draws unmistakably from militant political Islam. In a republic almost evenly divided between Muslims and Christians, and layered with ethnic complexity, the fusion of religion and state is combustible. Nigeria’s fragile nationhood rests upon the secular principle that the state belongs equally to all its citizens irrespective of creed. When that principle erodes, so too does the idea of a shared civic destiny.

This is why the ideology itself must be confronted, not merely the men who wield its weapons. Counterterrorism cannot be reduced to kinetic operations. It must also be intellectual, theological and civic. The merchants of absolutism, those who romanticize a theocratic state and delegitimize pluralism, must be challenged in universities, mosques, churches, media platforms and classrooms. The war against terror is as much a battle of narratives as it is a battle of arms.

The global dimension of this struggle inevitably draws attention to Turkey and underscores the strategic significance of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s recent state visit. Modern Turkey, forged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was transformed into a rigorously secular republic. For decades, it stood as living proof that a Muslim-majority nation could uphold institutional secularism while preserving its rich cultural and religious heritage.

Yet under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the aegis of the Justice and Development Party, Turkey’s ideological compass has shifted. Ottoman nostalgia has been revived, religious education vigorously promoted, and Ankara has increasingly positioned itself as a custodian of Muslim interests on the global stage. Although the Turkish constitution retains its formal commitment to secularism, the nation’s political rhetoric, public symbolism, and international posture now unmistakably amplify the visibility and influence of political Islam worldwide.

Nigeria’s engagement with Turkey is multifaceted and strategically significant. Cooperation spans trade, infrastructure and defense. Turkish manufactured equipment has supported Nigeria’s counterinsurgency efforts. Yet serious allegations have surfaced in recent years, including reports of intercepted shipments of hundreds of pump action rifles reportedly originating from Turkey in 2017, and claims denied by Ankara of links between Turkish channels and arms flows into Nigeria. Allegations are not adjudications. Nonetheless, when Nigerian villages are reduced to charnel grounds, even the perception of ambiguity demands rigorous scrutiny.

President Tinubu’s diplomatic engagement with Ankara should therefore transcend ceremony. True partnership requires transparency. If Turkey seeks to be an enduring strategic ally, it must demonstrate unequivocal commitment to ensuring that no private or clandestine networks within its jurisdiction facilitate violence in Nigeria. Equally, Nigeria must articulate its concerns with clarity and firmness, recognizing that security cooperation is inseparable from ideological accountability.

Woro’s massacre underscores a sobering reality. Terrorism in Nigeria is not merely a security problem but a philosophical one. The ideology that sanctifies the merger of religion and state is incompatible with a multi ethnic, multi religious and culturally pluralistic world. A modern nation cannot endure if one segment insists that divine mandate supersedes constitutional consensus. The fight against terror must therefore be multi-pronged. Military vigilance, intelligence reform, border control, economic development and above all ideological counteroffensive are all essential.

The dead of Woro cannot be restored to life. But their memory imposes an obligation. Nigeria must not content itself with reactive force. It must confront the intellectual architecture that justifies the machete and the rifle. In a republic as diverse as ours, secularism is not hostility to faith. It is the only mechanism by which faith can coexist without tyranny.

If the embers of political Islam that were ignited in the aftermath of 1967 are allowed to smoulder unchecked, they will continue to consume fragile societies. Nigeria must choose instead to defend the principle that the state belongs to all and that no ideology, however sanctified, may claim exclusive dominion over the nation’s soul.