By Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo

“Do you have a story?” Grandpa would ask anyone who visited him, testified his son-in-law, Sam Maduegbuna. He loved stories. If you rushed, he would ask you to slow down. If you didn’t tell it well, he would say, “You don’t know how to tell a story.” For him, it was not enough to have a story; you had to know how to tell it well.

In October 2014, many people stood up in a chapel and told stories about him. His doctor. His daughter. The pastor of the church he attended when he visited America. Those he had known since childhood and whose progress he had followed throughout his life. His neighbors. And all the others in between.

As diverse as the group that paid tribute was, the impressions everyone had of his life were the same: honesty, caring, simplicity, and hard work.

If someone compiled his biography from the stories told about him, the only suitable title would be A Good Life. It is not a title many people give their autobiography.

A young man recounted how he visited Grandpa with his daughter. The young man said that the 90-year-old grandpa paid more attention to his daughter, playing with her and listening attentively to what the little girl had to say. On their way home, the daughter turned to the young man and said, “Grandpa is a good boy.”

Chike Ofodile was a good boy.

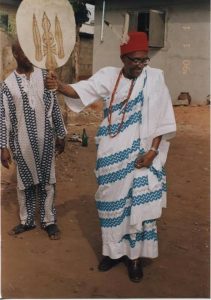

I did not meet him in life, but his daughter is a family friend. From the testimony of those who knew him, I had no doubt that he was. That he was one of the most successful lawyers in Nigeria, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria, a former Attorney General of Nigeria, and a Minister of Justice did not factor into the recollections of those who knew him. In video clips of his life, there were no clips of him giving orders or displaying power as Attorney General. There was no picture of him with any president. Instead, you see him with his grandchildren, stepping out of a car to enter the church, and his wife affectionately wiping food particles from his mouth. Several times, you see him dancing at one event or another in his full regalia as the Onowu of Onitsha. He loved tradition—the rich Onitsha tradition, everyone said—while still being a dedicated Christian. He saw no contradiction between the two.

After attending that beautiful memorial service in Youngstown, New York, for Chike Ofodile in October 2014, I asked myself: What will people say when I die?

And I ask you the same: What will people say when you die?

“The history of the world,” Thomas Carlyle said, “is but the biography of great men.” Benjamin Franklin added it is easy to make history. “Either write something worth reading,” he suggested, “or do something worth writing about.”

Unfortunately, history will not remember most of us. But the people who came in contact with us will. They are the historians who will tell our story. Though unwritten, their memories will remain, transmitted, and downloaded each time they recount it or others retell it.

The life of Chike Ofodile, as recalled by those who knew him, made me picture him as a man who had reached the peak of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. He had attained the self-actualization pinnacle of human existence. It reminded me of what I still consider the greatest challenge for African men and women—to take a step up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Most of us are still stuck at the lowest three levels of the pyramid. We are preoccupied with our pursuit of what Abraham Maslow called physiological needs, safety needs, and the need for love and belonging. These include breathing, food, water, sleep, sex, home, security of body, employment, health, resources, property, family, and morality. Others include friendship, family, and sexual intimacy.

This is why most of us define ourselves by the clothes we wear, the car we drive, the house we live in, the food we eat, the companions we have, our jobs, and the clubs we belong to.

People who have reached the upper levels of the pyramid focus on esteem and self-actualization. At this level, concerns shift to self-esteem, confidence, achievement, respect for others, respect from others, morality, creativity, spontaneity, problem-solving, a lack of prejudice, and acceptance of facts.

Those at this level measure their accomplishments differently from most of us. That is why one of the richest men in the world, Warren Buffett, still lives in the same home in Omaha that he bought in 1958 for $31,500. For that reason, Microsoft founder Bill Gates wears a $10 wristwatch. That is why Mark Zuckerberg often wears a simple shirt and jeans.

It is those of us who have not achieved true fulfillment who live in million-dollar houses, wear watches worth tens of thousands of dollars, and buy shoes that cost more than a year’s salary for most workers. We do so because we have not yet reached the level where we define ourselves by who we are, what we do, and what we contribute to humanity.

Do you care what people will say about you when you die? Will it be a factor in what happens thereafter? Does it matter even if you are heading to heaven?

Despite what our faith told us, we have no proof about where we go when we die. We can proclaim it all we want, but it doesn’t make it a certainty. What is certain is that people will pass judgment before the final judgment comes. What will their assessment of you look like? Will people remember you as a good boy or a good girl?

Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo teaches Post-Colonial African History, Afrodiasporic Literature, and African Folktales at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He is also the host of Dr. Damages Show. His books include “This American Life Sef” and “Children of a Retired God.” among others. His upcoming book is called “Why I’m Disappointed in Jesus.”