By Nnamdi Elekwachi

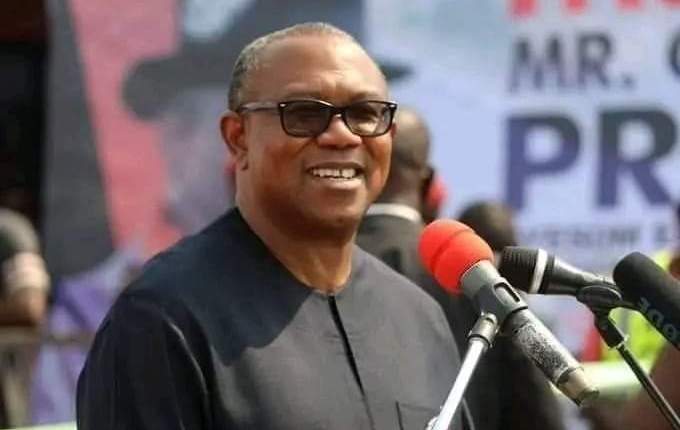

The generally held notion that the Igbo are inherently apolitical is receiving a sharp contrasting twist with the Peter Obi presidential candidacy. Even Nigerians of other ethnic affiliations, mostly the youth who held no PVCs before now, are radically joining the ranks too, showing their overwhelming support for the Obi candidacy. Of late, there’s an unheard-of level of mobilisation among the hitherto ‘apolitical’ Igbo that is now moving them, their entire consciousness and collective aspiration to the centre – a centripetal pull one might say.

Not Obi himself could tell how all of a sudden he became such a political firebrand and rallying point for the Nigerian commons, having been part of the establishment from the get-go of his political sojourn. If he ever knew, he wouldn’t have wasted his time and dime in PDP touring over thirty states, canvassing delegates the last few months.

As part of my right to education, I still insist on being lectured by this school of thought whose assumptions about the Igbo are premised on the doctrine of inherent apoliticism. And as I am wont to ask: which human society, even in its darkest, crudest stage, naturally lacked a centralised or decentralised formation, a kind of administrative setup evolved to execute its goals whether by force or fiat no matter how obsolete or imperfect the machinery it deployed? Nevertheless, many factors – both internal and external – contribute to pushing a human group, in this case the Igbo, away from integrative politics to seeking a separate existence outside a space which they share as a group with others, especially when they consider as lowly their political station and status in the said space.

Though the Igbo have their peculiar problems (they are many, to which I shall return), yet in any group setting or, say, group discourse that centres Nigerians, they are conveniently reduced to a subject of collective odium as being, ‘grabby,’ ‘avaricious,’ ‘opportunistic,’ even ‘ritualistic’ sometimes. This odium, recently, was being churned out from pulpits of churches owned by certain Yoruba pastors, one of them being a presidential aspirant who claimed God had told him he was the next Nigerian president after Buhari. From their vaulted sanctuaries, these clergymen had labeled the Igbo race ‘cursed,’ ‘stingy,’ etc.

It yet remains an incontrovertible fact of history that in all the political phases of Nigeria, from colonialism in 1900 to flag independence in 1960, the Igbo, just like other Nigerian tribes, played a decisive part. To make it clearer, 1960 would not have happened for Nigeria in the manner it did had Azikiwe not agreed to form a coalition with Balewa’s NPC; it wouldn’t have been easier either had the same Azikiwe not been at the vanguard of independence march. Not even 1999 transition would have been that smooth and seamless had the Igbo not played a part like other groups too.

On 1999 I wish to dwell a bit

Recently, during the APC special convention, Dr. Ogbonnaya Onu, a party chieftain of Igbo extraction, reminded President Buhari and by extension other party bigwigs how he (Onu) singlehandedly registered the APC under INEC with his money. What does that really say? Simply put, Onu, who, unlike Tinubu and Buhari, had control of no state government at that time, formalised a mere coalition – which APC was then – as a political party properly so called.

In their existence or operation, political associations or coalitions cannot be accorded the status of a political party until registered duly under the law to exist for the very purpose of participating in periodic elections, gaining political power and forming a government thereafter. Although other allies within the coalition could have registered it formally as a party still, in a strictest sense, Onu earned APC its political status as we have it today and so should stand as one of its major stakeholders when it comes to the spoils.

As the APP presidential candidate during the 1999 transition, Dr. Ogbonnaya Onu, had recounted countless times how he had to collapse his campaign and sink his ambition so that a candidate of Yoruba origin – Chief Olu Falae – could emerge through a compromise the nation had reached when the Yoruba West threatened to leave her and face the Atlantic after the mysterious death – in custody – of Chief MKO Abiola, the acclaimed winner of the annulled June 12 presidential election in 1993. Another Igbo who deserves a mention having sacrificed his presidential ambition in 1999 is the former governor of Anambara State, Chukwuemeka Ezeife, then of Alliance for Democracy, AD, who was with the late MKO Abiola in the SDP. Ezeife, like Onu, stepped down for Falae. As for the PDP where Alex Ekwueme and other Nigerians formed the G34, an association that later morphed into a party that would control government in Nigeria for sixteen years, the rest, as they say, is history.

Now to the questions: what exactly did the duo of Onu (APC) and Ekwueme (PDP), both of Igbo extraction, get as reward for being loyalists to their respective parties? Did they not contribute to laying the groundwork for the emergence of their parties’ candidates in 1999 and by extension to the smooth and peaceful democratic transition that same year and even afterwards?

Now to the Igbo question. If indeed charity begins at home, then the Igbo problem should first be reviewed therefrom.

Most Igbo today are eager to point to external factors, like marginalisation by successive federal governments, as chiefest of their problems, but within, there are other challenges, even internal contradictions plaguing the Igbo. There is political elite corruption and leadership inertia deepening apathy among her regional populace, the youth for the most part. Leadership inertia among the Igbo followed the decades after the ‘Biafra War.’ Since then, the Igbo have had it both rough and tough, only taking to their republican and individualist nature buoyed by survivalist spirit to pull through.

Although the Igbo thrive on republicanism, there is leadership vacuum unlike in the days of Nnamdi Azikiwe (1940s to late ‘50s); Michael Okpara (late ‘50s to mid ‘60s); and Emeka Ojukwu (mid ‘60s to 1970) – all with whom the regional politicians of today cannot be compared. The effect is manifest in lack of a common front and consensus through which to mobilise owing to the unpopularity of virtually all Igbo sons and daughters elected into state and federal positions or appointed thereto; quite contrary to the age-old Igbo philosophy of Igwe bụ ike (communalism). Achebe, who identified ‘rugged individualism’ as something also inherent in the Igbo had equally observed that as free spirits, their individualist worldview brings the Igbo into constant conflict with other Nigerian groups, especially their hosts of other tribes with highly centralised religio-cultural formations. The Igbo, likely the most daring of all Nigerian groups, hardly bend.

Political elite corruption is a serious factor bedeviling the Igbo too, though it equally affects other Nigerian groups. Today, the five regional governors in the South-East cannot match Okpara’s sterling records nor near the innovative breakthroughs recorded under Ojukwu even with their statutory and independent revenues over political units smaller than what Okpara and Ojukwu administered (nine states now) decades after.

There is propagation of secessionist agenda by MASSOB and IPOB, sometimes too by other faceless separatists whose campaign for a plebiscitary restoration of a sovereign state of Biafra became a rallying point for the disillusioned youth; a movement that has fueled apathy today and reached a fever pitch under the current Buhari-led government. In 2006, MASSOB, a pro-Biafra secessionist group agitating in the South-East, placed a boycott on the population census being conducted by the Obasanjo-led federal government. The result of boycotting that headcount, in addition to producing a poor demographic data on the five Southeast states, is that since population remains one of the criteria for revenue sharing, state creation and constituency delimitation, the Igbo, with paltry five states, got the least in terms of statutory revenue and legislative seats. When IPOB proclaimed ‘No election in Biafraland,’ it meant not only self-exclusion but equally a political relegation of the South-East since it barred the people in the region from voting out bad and corrupt leaders across the five states. Is it any wonder leaders in the region work to always sustain youth and/or political apathy?

Before I talk about secession, it is important to give at least a passing mention to the external problems facing the Igbo. Ranking top is the suspicion which other Nigerian groups have for the Igbo. This suspicion and fear, which existed before 1960, only got worsened by January 15, 1966 military putsch said to have been perpetrated by Igbo military officers. Not even the counter coup of July 1966 by young northern officers doused this suspicion which became fiercer during and after the civil war. This suspicion is largely the reason President Muhammadu Buhari, who held command and commission during the civil war, would never have an Igbo in his security cabinet today, even as a democratically elected president. In fact, the narrative, though entirely wrong, is that the Igbo had solely staged the coup of January 15, 1966 to neutralise politicians of other tribes, control political power and dominate all of Nigeria. Due largely to this, to eliminate the Igbo from Nigeria’s political and economic equations appears to be the common good for successive Nigerian governments.

On the civil war, it serves posterity better to put the record straight. What today is known as ‘Biafra War’ was a revolution by some nationalist officers, in some cases adventurists with a little of Marxist leaning, trying to address a regional inferno in the Yoruba west that was consuming the fledgling nation. Participants in that coup later revealed in their military and war memoirs that the goal was to install Chief Obafemi Awolowo, a democratic socialist of the Fabian Society, as the president. It remains an inexplicable twist that when the major cataclysm came in the form of war, only the Eastern region suffered it as a theatre.

It was quite ironic that the same Chief Obafemi Jeremiah Awolowo, whom the so-called ‘January boys’ had wanted to install in 1966, while serving as the finance minister in Gowon’s war cabinet and also shortly after the war would introduce his £20 recompense policy for all Igbo pre-war bank account holders regardless of their initial deposit. This, perhaps to the Yoruba chief, meant a Marshall Plan for an Igbo recovery. However, the post-war recovery of the Igbo from this and other numerous harsh economic policies took Nigeria’s suspicion up a notch decades following the war. Abandoned property saga too remains indelible in the hearts of many Igbo whose properties were appropriated by other Nigerians resulting in final loss except in places like Lagos where Yoruba hosts returned Igbo properties to them after 1970. The 1976 Mamman Nasir Boundary Committee ceded many Igbo-speaking areas to other Nigerian groups where they ended up as minorities in Rivers, Delta and other adjoining states. Quota system, federal character principle, catchment area policy and the rest are in the mix too. But it is equally vital to state that since they are the most itinerant of Nigerians, the Igbo are arguably the most welcomed in a sense.

Secession? There is nothing wrong with the word ‘secession,’ not even by extant public international law standard is anything wrong with it. About secession in Nigeria let a few things be said. During the constitutional conference of 1950 that preceded the MacPherson Constitution of 1951, Chief Obafemi Awolowo of the Action Group had proposed that secession clause be inserted into the framework of the constitution. Even though Awo’s fear hinged on the status of Lagos which Eastern delegates said was ‘no man’s land’ and therefore should not be administered as part of the West but separately as Federal Capital Territory, the Yoruba chief was bluntly told by Azikiwe that ‘secession is against the federation.’ Chief Awolowo, to whom Nigeria made only a geographic sense, saw things differently from Zik who started out as a pan-Africanist and broad-minded nationalist. What has to be strongly said however is that there was no justification for the claim of Lagos being a ‘no man’s land’ as was first advanced by Jaja Wachuku, an Igbo in the late 1940s. Lagos belongs to the Yoruba!

The first traces of separatism could be found in the words of late Sir Ahmadu Bello, former premier of Northern Nigeria. Writing in his autobiography, My Life, Bello averred:

‘Lord Lugard and his amalgamation were far from popular amongst us at that time. There were agitations in favour of secession; we should set up on our own; we should have nothing more to do with the Southern people…’ (pp 134/5)

The Sarduana, here, in his own words revealed how the North had wanted to secede from Nigeria as early as 1914. In fact, it took British influence to convince the North to stay in the union.

In a polarised multi-ethnic federation, especially the Nigerian type with ethnic majorities and minorities, the option of secession is often allowed because it creates necessary balance and boundary and as well checks the domination of minorities by the majorities. But the question I often ask is: why is it that the Igbo, who were not the first to threaten secession or call for referendum (considering Southern Cameroon case in 1961), and whose marginalisation speaks volumes continue to suffer collective antipathy to date?

The terror-related activities allegedly being perpetrated in some quarters by IPOB’s armed wing, ESN and other faceless separatists in the region, are the result of Buhari’s mismanagement of what existed before him; what Obasanjo, Yar’Adua and Jonathan saw with MASSOB and IPOB but approached rather differently. In 2016, in Aba, the Nigerian military had opened fire on unarmed IPOB members who had gathered to pray at a secondary school. There was no reason given for the killings whatsoever. The same thing happened in Emene, Enugu where the group were having their meeting. To worsen the whole case, Buhari adopted maximum force, placing the entire Southeast under military jackboot in the name of an operation code-named ‘Python Dance II’ just to contain an unarmed separatist group! Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and other rights groups reported the state-sponsored killings by Nigerian security agencies during that period, Nigerian government ignored the concerns raised against the massacre of its own citizens it had sanctioned. It was after the Emene killings that IPOB began chanting ‘to arms!’; today, the rest is history.

Provincialism is both systemic and endemic in the Nigerian polity where ethnic groups are drawn in infighting, each with inordinate quest to outmanoeuvre the other. A crab mentality too is forcefully at play fueling this unhealthy competitiveness. The thinking is: ‘if my ethnic group can’t have it, neither yours can.’ So 2023 presidential election stages a re-enactment of the Nigeria of the ‘60s where the dominant political parties were nothing more than hothouses for nurturing ethnic agenda. The trio of Abubakar Atiku, Peter Obi and Bola Ahmed Tinubu of the PDP, Labour Party, and APC present the Nigerian electorate another version of NPC, NCNC and AG (not really disregarding Rabiu Kwankwaso of the NNPP and other presidential aspirants). In the ensuing bickering, the Igbo and Yoruba, in a bid to sell their candidates, are falling out on social media platforms, attacking themselves. Recently in Lagos, the attack took a physical dimension when a nameless Yoruba mob injured Igbo residents who had turned out en masse to get their PVCs at registration centres. It reminded one of a certain Oba Akiolu in the same Lagos who once threatened to drown the Igbo in lagoon during 2015 gubernatorial election.

Let it be said that had politics in Nigeria any moral bearing and were the issue of power rotation among geopolitical zones supreme, regardless of whatever gentleman’s agreement Tinubu may have struck with anybody, the Yoruba, having enjoyed for two tenures the positions of president and vice, have no business vying for the presidency in 2023. Barring the Igbo of the South-East – who came closest to the presidency during the 1979-83 Second Republic with Alex Ekwueme as vice president – the other two Souths have held the position of the president and that of vice respectively since 1999. This whole argument about power rotation later narrowed the debate from zoning down to ‘micro-zoning’ in favour of the Igbo and at the end, the latter option was jettisoned by both the PDP and APC where the Igbo had made sacrifices for Yoruba presidential candidacy and significant contributions also. Not even calls for a Nigerian president of Igbo extraction by southern statesmen like Edwin Clark and Ayo Adebanjo of the Afanifere group were heeded by both parties.

If there was any unforgivable sin of betrayal committed against the Igbo over how presidential flag bearers of the two major parties emerged, PDP’s case was the gravest given that the stake of the Igbo in APC, which by far remains less popular within the South-East political base, pales in comparison with their stake in the PDP where they had pitched their political tent since 1999. Worst was that the PDP whose constitution provided for zoning and rotation of power strategically went against its own creed by auctioning off its presidential ticket to the highest bidder. While it is true that the North-East to which the PDP zoned its presidential ticket is yet to have a stint at the presidency, returning power to the same North, whether east or west of it, after 8 years of Buhari presidency should not have been an agenda of any party guided by the principle of equity or fairness.

Today, Obi appears unduly simple, parsimonious but yet self-assured. His popular acceptance within the Igbo voting bloc and other ethnic groups does not sit well with certain camps, mostly the APC pro-establishment forces of the ‘dirty-fighting’ Yoruba whose major claim to the presidency is a matter of entitlement, right and patent. There is a question and hope in all of it. The question is: will the emergence of Mr. Peter Gregory Obi, beyond realising the first Igbo presidency to which the likes of Zik and Ekwueme aspired before, reconcile the Igbo with other Nigerians and settle the ‘consensus of resentment’ Achebe once wrote about in the early 1980s? Will it settle the 1966-70 question?

While the Igbo mobilise for Obi, there is a kernel of hope that perhaps 2023 could well be an era the South-East changes the narrative and perhaps go one better in addressing the problem of failed leadership across its five states by participating in its own electoral affair. Maybe this, in addition to raising the Igbo consciousness, is what the Obi candidacy will bring; hope!

Nnamdi Elekwachi, a historian, can be reached via nnamdiaficionado@gmail.com