Introduction:

Born on December 12, 1958, Senator Hope Odidika Uzodimma became the Governor of Imo State on January 14, 2020, through what many described as a controversial judgment of the Supreme Court of Nigeria. Uzodimma, who had come a distant fourth in the polls, replaced Gov. Emeka Ihedioha of the Peoples Democratic Party, PDP, whose election was nullified by the apex court. On November 11, 2023, Uzodimma, a former Senator who represented Orlu Zone in the 8th Senate, was re-elected Governor for a second term in office under the platform of the ruling All Progressives Congress, APC. He took the oath of office for his second term on January 15, 2024.

Preamble

In this investigative report carried out by Ikengaonline (a non-profit media organisation dedicated to public accountability and good governance) in collaboration with Dataphyte (a data analytics company), with the support of the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism, WSCIJ, the four-year administration of Governor Uzodimma was examined. Important metrics were evaluated to determine the effects of Uzodimma’s administration on the people.

Mode of Data Collection

Data for the investigation were collected using various processes and methods, including but not limited to site visits, inspection of documents, review of government records under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act, interviews, and testimonials. Where necessary, experts were engaged to help dissect the subject.

The pool of data collected in the course of this investigation was further subjected to thorough analysis by relevant experts and stakeholders, comprising a team of policy experts, seasoned journalists, and representatives of Civil Society Organisations, as well as other relevant bodies. A three-tier scoring system was adopted to rate Uzodimma’s overall performance in each of the eight key sectors assessed. Consistent with investigative journalism best practices, the goal is to present the facts objectively without compromising sources and methods.

Summary of Performance

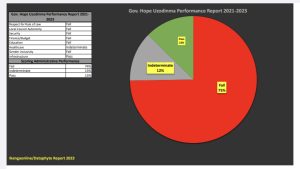

Governor Uzodimma’s performance was evaluated across eight critical sectors, collectively representing the entire scope of the research (100%). Like the immediate-past Governors of Abia (Okezie Ikpeazu) and Enugu State (Ifeanyi Ugwuanyi), who failed woefully in almost all the metrics, Uzodimma also posted abysmal performance, failing in six categories except in Infrastructure where he got a Pass. Score on Health was indeterminate. Thus, for a total of 100%, he scored: Pass: 12.5%; Fail: 75%; and Indeterminate: 12.5%.

Indeterminate means that the results were inconclusive and couldn’t be definitively classified as a pass or a fail. This is unlike ex-Gov. David Umahi of Ebonyi State, who scored a pass in three of his nine categories representing 33%, and Gov. Chukwuma Soludo of Anambra State, who got a pass in four of the nine sectors representing 44.4%.

Sector by sector performance

SECURITY

In the course of the investigation, it was discovered that Imo State under Governor Uzodimma, became a theater of war and a slaughter ground. Hardly did a week pass even as at the point of filing this report, without any incident of killing or barbaric attack on either innocent citizens or security operatives by non-state actors that had and still have their enclaves in parts of the state.

The tenure was characterised by incessant gunmen attacks leading to loss of many lives and property of inestimable value. Security agents were fingered in some of the killings. Some of the atrocities were committed under the guise of hunting for hoodlums or a clear case of reprisal attacks.

Imo State has been marred by a series of security challenges, including the notorious Owerri Correctional Center attack in April 2021, which saw 1,844 inmates released. The masterminds remain disputed, but insecurity persisted, with unknown gunmen, state-backed outfits, and non-state actors contributing to a wave of violence. High-profile figures, security personnel, and innocent citizens fell victim to targeted attacks, leading to reprisals, military raids, and escalating tensions. Imo grapples with an alarming security situation, complicated further due to alleged state-sponsored actions.

LOCAL COUNCIL AUTONOMY

On March 12, 2022, Governor Uzodimma conducted a local government election, which was won by his party, APC, in all the 27 local government areas of the state. However, analysts and many stakeholders viewed the election conducted by Imo State Independent Electoral Commission (ISIEC), as not meeting the thresholds of free and fair election but a mere selection process to plant the governor’s surrogates at the local council level in preparation of his re-election in 2023.

In any case, findings show that Imo State’s Local Government system lacks financial autonomy, remaining tethered to the control of the State Government through Joint Accounts. Despite calls for autonomy, the State House of Assembly, led by Rt. Hon. Emeka Nduka, vehemently opposed Local Government autonomy during the January 2023 amendment of the 1999 Constitution. This decision, widely perceived to align with the state Governor’s influence, has sparked criticism, with many viewing it as a setback for those advocating for Local Government autonomy to expedite rural development.

RESPECT FOR RULE OF LAW

Governor Hope Uzodimma of Imo State enacted the Imo State Administration of Criminal bill No 2 of 2020, granting him the authority to detain individuals without a court warrant. This law although seems to follow a similar one at the federal level, stirred controversy for its perceived draconian tone and infringement on citizens’ rights to fair hearing, receiving backlash from Imo citizens.

Again, despite assurances, reports from investigative panels and judicial commissions set up by the former governor, Emeka Ihedioha, including the Justice Benjamin Iheaka-led Commission on Contracts and the Judicial Panel on Lands, have not been made public by Uzodimma’s administration. Allegations of political vendetta surround the seeming special attention given to the report on former Governor Rochas Okorocha’s administration.

Uzodimma’s administration has a history of disobeying court orders, notably in the case of a N1.9 billion judgment debt in favour of former Deputy Governor Eze Madumere. The government’s resistance led to an attack on National Industrial Court staff, resulting in the closure of its Imo division.

Similarly there are allegations that Governor Uzodimma was using his office to intimidate political opponents by way of illegal sealing off and/or demolition of their business premises even with proof of valid C/Os issued by the Imo State Government. Another incident involved the assault on the National President of the Nigeria Labour Congress during a rally, reflecting a disregard for the rule of law.

GENDER SENSITIVITY IN POLITICAL APPOINTMENTS

Investigation reveals a lack of gender sensitivity in Gov. Uzodimma’s political appointments. While women initially secured five out of 18 Commissioner slots in November 2021, subsequent appointments witnessed a decline. Among the 81 Special Advisers later appointed, only 14 were women. In April 2021, Uzodimma appointed three women as Transition Committee Chairmen for the 27 LGAs, but in July 2022, he replaced them with 27 Sole Administrators, allocating only two slots to women. By July 2023, the swearing-in of 247 Special Advisers saw women constituting less than 25% of the new appointments.

Despite criticisms of gender insensitivity, Governor Uzodimma appointed a female Deputy Governor in his second tenure. While some commend this as a positive step for women in politics, others remain skeptical, citing the historical under-representation of women in his previous appointments.

FINANCE

Budget:

In 2019, the state’s budget surged from N130.40 billion to N276.82 billion, with capital expenditure constituting 77.54 percent, while recurrent expenditure comprised 22.46 percent. In 2020, the state witnessed its smallest budget at N108.39 billion, with approximately N44.79 billion allocated to capital expenditure and N63.42 billion to recurrent expenditure.

Following the contraction in the state’s budget in 2020, subsequent budgets exhibited an upward trajectory. The 2023 fiscal year marked the highest budget within the reviewed period. Out of the N474.47 billion approved for 2023, 78.73 percent was designated for capital expenditure, while 21.27 percent was allocated to recurrent expenditure.

In the reviewed period, excluding 2020, Imo State consistently directed a significant portion of its budget toward capital spending. In fact, apart from 2018 and 2020, no less than 73 percent of the state’s annual budget was allocated to capital expenditure

IGR:

Stears Inc, an organization that provides economic and industry data & insight to facilitate decision-making for global organisations investing and operating in Africa noted that one of the methods economists use to assess a state’s capability for long-term economic activities, such as boosting employment and providing efficient public services, is by evaluating its independent revenue generation.

A state’s Internally Generated Revenue (IGR) serves as a key indicator of its financial strength and ability to function independently, without relying solely on allocations from the federation account. States typically generate IGR through various means like Pay-As-You-Earn Tax (PAYE), direct assessment, road taxes, and revenues from certain ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs). According to National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data, Imo State accumulated a total IGR of N59.68 billion between 2015 and 2021.

Imo State witnessed an increase in its IGR from N5.47 billion in 2015 to N14.88 billion in 2018. However, there was a notable drop in 2019, with the state’s IGR falling from N14.88 billion in 2018 to N6.18 billion, indicating a 58.46 percent decline. Subsequently, there was a rebound in the following years, including 2021. Nevertheless, the state has yet to surpass the N14.88 billion mark achieved in 2018.

Federal Account Allocation (FAA)

Another crucial indicator to scrutinise is the amount the state has received as allocation from federal account between 2015 and 2021. Data gleaned from the NBS shows that, in the period under review, Imo State received N294.88 billion. In 2015, the state received a total of N39.48 billion as FAA. In 2016 and 2018, the state’s allocations were N30.20 billion and N38.12 billion, respectively. From 2018, the state witnessed an annual increase in its FAA, except for a slight decrease in 2020. Nevertheless, the allocation remained at least N55 billion.

The highest FAA the state received in the period under review was in 2021 — N60.56 billion.

Debt Profile:

Dataphyte’s analysis of Imo State’s debt profile from 2015 to 2022 reveals a significant reliance on borrowing, particularly from domestic sources. At the close of December 2015, the state’s domestic debt amounted to N71.74 billion, based on data from the Debt Management Office (DMO). This figure rose to N93.27 billion the following year, with a subsequent 13.38 percent decline in 2017. However, in 2019, there was a renewed increase in debt. By the end of 2022, the state’s domestic debt had surged to N204.22 billion, marking an almost 185 percent increase compared to the 2015 figure.

With its current debt status, Imo ranked as the 6th state in Nigeria with the highest domestic debt at the close of 2022. In terms of foreign debt, the state held the 24th position among the most indebted states. Starting from $59.16 million in 2015, the state’s foreign debt reached $96.12 million in 2020. However, by the end of 2022, the state’s foreign debt had decreased to $51.09 million, marking its lowest recorded level in the period under review.

EDUCATION:

Education Budget

Investing in education is widely recognised by experts as crucial for accelerating the economic growth of any society. Over the years, there has been a persistent call for governments to enhance funding in the education sector. A scrutiny of the Imo State budget from 2018 to 2023 discloses that the state dedicated a total of N161.72 billion to its education sector during this period. In 2018, the sector received a budgetary allocation of N20.32 billion, which saw an increase to N23.88 billion in 2019.

The allocations for the education sector experienced a decline in 2020 and 2021. However, there was a significant upswing in 2022, with the state allocating N53.80 billion to education. In contrast, the allocation for the education sector in 2023 decreased to N17.15 billion. Notably, except for 2020, Imo State consistently kept its education budget below 15 percent throughout the reviewed period. In 2020, the state allocated a noteworthy 21.91 percent of its annual budget to education.

Days out of school (Strikes):

Between 2015 and 2022, public universities in Imo State, Nigeria, faced three strikes, causing academic disruptions totaling 492 days. In 2018, an Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) strike spanned 94 days, followed by a 120-day strike in 2020 and an 8-month strike in the subsequent year. This impacted the educational continuity of students in the state.

Performance in national examination (WAEC)

Analysing the performance in the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), in 2016, 70.89 percent of the 45,050 students from public and private schools in Imo State passed the exam. The pass rate increased to 76.76 percent in 2017 but slightly dropped to 74.10 percent the next year. However, 2019 marked an improvement, and 2020 saw further progress. Unfortunately, there was a decline in 2021. In Unified Tertiary Matriculations Examination (UTME), Imo State achieved its best result in 2019, with a student scoring 347. Notably, since 2019, the state consistently maintained over an 80 percent pass rate in UTME.

Number of out-of-school children:

In 2018, Nigeria had 10.19 million out-of-school children, according to NBS data, with Imo State having 275,890, the highest in the South-East. Among them, 243,433 were male, and 32,457 were female. No additional data has been released by the NBS since 2018.

However, a 2022 report by The Guardian revealed a significant decrease, indicating 125,414 out-of-school children in Imo State—a 48.48 percent reduction. This positions Imo State as the second-highest in the South-East for the number of out-of-school children.

HEALTH

Healthcare budget:

Between 2018 and 2023, the health sector in Imo State received a total allocation of N76.96 billion. The yearly budgetary allocations varied, with N13.31 billion in 2018, the lowest of N10.46 billion in 2019, and a peak of N17.95 billion in 2022.

Health coverage in the state reveals low insurance rates, with only 3.1 percent of women and 9.7 percent of men aged 15 to 49 covered. For children under five, the coverage is 4.2 percent, and for those aged 5 to 17 years, it is 3.2 percent. In terms of service delivery, Imo State ranked the lowest among South-East states from 2019 to 2021, according to the ONE Campaign.

Governor Uzodimma’s commendable efforts include the construction of three ultramodern hospitals in Oru East, Ohaji/Egbema, and Oguta. Equipped with modern facilities, these hospitals aim to enhance accessibility to quality healthcare in the state’s oil-producing Local Government Areas.

Doctor-to-patient ratio:

The brain drain (japa) syndrome has led to a shortage of manpower in the health sector, resulting in a low doctor-to-patient ratio across many states in Nigeria, including Imo State.

In 2018, Imo State had 528 doctors, translating to a doctor-to-patient ratio of 1:10,921 based on the estimated population of 5.77 million. In 2019, this ratio worsened with 332 doctors and a population increase to 5.95 million, resulting in a ratio of 1:17,933. By 2020, the ratio dropped further to 1:19,830.

Regarding public health facilities, Dataphyte’s report revealed that many Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) in Imo State lack essential utilities, placing the state at the bottom in terms of primary healthcare facility conditions. Another report highlighted a significant shortage of medical personnel in numerous PHCs.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Despite challenges, Governor Uzodimma’s first term demonstrated notable achievements in infrastructural development, encompassing the rehabilitation of over 40 urban and rural roads, including the Aba Branch-Ahiara junction, Nkume-Umuowa Orlu, and rehabilitation at both ends of the airport road. (Rehabilitation works on some of the roads have not been completed)

Urban roads, such as Dick Tiger Road, Relief Market Road, and Musa Yar’adua Drive extension to Dream Land Hotel Road, were rehabilitated. The tenure also witnessed the completion of the rehabilitation and dualisation of major arterial roads linking Owerri Capital Territory with other major towns in the region, including Owerri-Orlu road, Owerri-Okigwe road, Owerri-Aba road, and Owerri-Umuahia road.

Governor Uzodimma inaugurated the Imo State Court Complex in Omuma, Oru East Local Government Area, housing the State High Court, Magistrate Court, and Customary Court. Additionally, a new Executive Council chambers, Banquet Hall, and the State House of Assembly complex were rebuilt.

Despite the existence of the Imo State Water and Sewage Corporation, most residents rely on boreholes due to persistent water scarcity. The government’s 2020 announcement of the restoration of pipe-borne water in some areas did not last, and even the included areas did not enjoy it for an extended period.

Overall Performance

1 Respect for Rule of Law – Fail

2 Local Council Autonomy – Fail

3 Security – Fail

4 Finance – Fail

5 Education – Fail

6 Gender Inclusivity – Fail

7 Infrastructure – Pass

8 Health – Indeterminate

Scoring Administrative Performance

Pass: 12.5%

Fail: 75%

Indeterminate: 12.5%

Scoring System

Pass: When the administration is deemed to have performed creditably in a particular sector.

Fail: When the administration is deemed to have performed woefully in a particular sector.

Indeterminate: When the facts are not compelling enough to score the administration’s performance in that sector as a pass or fail.

A research by Ikengaonline in collaboration with Dataphyte under the auspices of the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ), this report was made possible through the generous support of John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.