By Rudolf Okonkwo

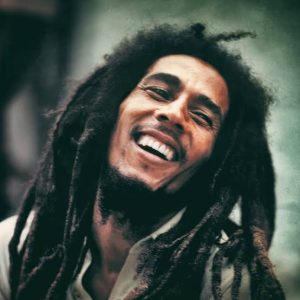

Growing up, I wanted to be Bob Marley. Nothing more, nothing less.

I bought every one of his cassettes I could see. I read and memorized the lyrics of his songs from those Onitsha market printed booklets that mangled the words of the reggae musician. I went as far as buying his interviews. Though it was challenging to understand Patwa, I enjoyed listening to Bob.

When I discovered I did not have Bob Marley’s voice or the vision, I decided to be Obi Egbuna, the George Bernard Shaw of our shore. I’m still working on that one.

But before I abandoned the Bob Marley dream, I had imbibed most of his philosophical musings -the desire to see equal rights and justice – and the advocacy for one Love.

I was fascinated by how Bob Marley transcended the ordinary in communicating deep levels of feelings and thoughts. The way he captured the fullness of a revolutionary spirit that transformed the mindset of millions.

Bob Marley brought something unique to the public space through music, dance, and chants – a commitment to the truth – undiluted and un-adulterated, of the ancient African spiritual force in us all. His dedication to his craft inspired all who wished to elevate their dreams. As a soldier in the battle to emancipate ‘the souls of black folks,’ he infused energy that kinetically emboldened the apostles of peace.

His music opened up access to a dormant part of my life. In his message, a version of my grandfather’s quest came alive. He transported the subliminal into the subconscious. Reading his imprint on the canvas in the sky, I unlocked the pool of foundational ignorance in which we swim. As a vessel of our ancestors’ cry, he sent out vibrations that bonded with ripples and traveled beyond the seven rivers and seas.

The complex simplicity of Bob Marley’s lyrics placed on notice ears that heard them. An honest interpretation of the truth of their mood and authenticity awoke the essence of our creation. Something phenomenal about him invoked beauty in those who found themselves in the presence of his influence and made it impossible not to embrace the healing cultural chasm he stirred up and placed on an overdrive.

As we celebrate the release of his biopic, Bob Marley: One Love, I remember that Bob Marley was once an immigrant like most of us, and America would have swallowed him in a rat race if he had not left Chrysler’s car manufacturing job he got in Delaware and returned to Jamaica to answer his calling.

At 11 a.m. on February 10, 1966, just four days after his 21st birthday, Bob Marley walked into the office of the Justice of Peace in Trench Town. He wore a black suit and the fancy shoes that music producer Coxsone bought for him. His bride was wearing a borrowed mother-of-pearl tiara and a white wedding dress made by her aunt. A few hours after the marriage, Bob Marley and the Wailing Wailers opened for the Jackson Five at the National Stadium in Kingston.

Two days later, he left Jamaica for Delaware.

His mother, Cedilla Malcolm Marley, immigrated to America three years earlier. She had filed papers for him to join her. When his papers came through, he said he would only leave if Rita would eventually follow him. He married Rita because he feared she would find another boyfriend when he was gone.

In Delaware, Bob worked at the Chrysler factory. He also worked at Hotel DuPont in Wilmington. He did not like what he was doing. He did not like life in America.

Eight months later, he wrote Rita, saying, “I’m coming home; I’m sick of this place. Today, while I was vacuuming, the vacuum bag burst, and all that dust went up in my face. If I stay here, this is gonna kill me. It will give me all kinds of sickness! I’m a singer, I’m not this, I’m coming home.”

Bob Marley returned to Trench Town and continued to work on his music. Things were tough. He had no money and shared a room with two kids at Rita’s aunt’s place. During this period, Bob and Rita began to practice Rastafarianism. They refused to eat from the same pot as Aunty, in whose house they lived.

That irritated Aunty.

Rita’s brother, Wesley, a police officer, was also furious about her belief in Rastafarianism. One day, he came home and beat up Rita, saying, “Do you think it is right, after all the money Aunty and I spent on you, that you end up like this? What are you getting out of it? You think because you’re married, you’re big? You’re still under our protection, and you have no right to be a Rasta! That’s being worthless.”

As a result of these developments, Bob and Rita decided to return to Nine Miles, a village in St. Ann, Bob’s birthplace. St. Ann had no electricity and no running water. Bob’s family house had no kitchen and no toilet. It was in a farm area on a hill.

On hearing that Bob was returning to St. Ann, his mother wrote from Delaware asking him to return to America for St. Ann would be his end. She urged Bob to be a gentleman, wear neckties, and work nine to five. “You are going back to careless life,” his mother wrote, “life that doesn’t show money making. You and Rita have no ambition.”

Bob and Rita lived in St Ann, working on the farm. During that period, Bob also wrote some of his most memorable songs.

In January 1967, Bob was introduced to Johnny Nash, who signed the Wailers to JAD records. That was how Bob Marley and the Wailers took off.

In 2000, Time magazine voted him the greatest musician of the 20th century, greater than Elvis, Michael Jackson, and the Beatles put together. His song, One Love, was voted the best of the century, and his album, Exodus, was the best album. At his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, U2’s Bono dubbed Bob “Dr. Martin Luther King in dreads.”

Though he died in 1981 from cancer, his album, Legend, has remained on the Billboard 100 chart ever since. Across the globe, anywhere oppression of the weak is taking place, courage and solace seem to emanate from his songs.

I was thirteen when I discovered him. It was at a high school send-off party where the DJ played Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldier.” In the song, he talked about being taken from Africa and brought to America. It was the first time I was aware that some people were taken from Africa and brought to America. No schooling up to that point had taught me that.

At sixteen, now in College, I heard Redemption Song. I wanted to grow my hair like his.

At twenty-six, I had immigrated to America like Bob.

At thirty-six, I read “No Woman No Cry? by Rita Marley and concluded that Bob became what he is today because he said no to America. Because Bob said no to America, he escaped what had become a wasted journey for so many.

Bob Marley would have been seventy-nine years old. Maybe if he had not said no, he would have been one of those middle-aged Americans whose jobs at Chrysler had gone to Mexico.

How has your journey been? What legacy are you leaving behind? Will your footprint on this earth join the legendary stream of one love running down to the delta of peace where the dignity of humanity is coming together?

Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo teaches Post-Colonial African History at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He is also the host of Dr. Damages Show. His books include “This American Life Sef” and “Children of a Retired God,” among others. His upcoming book is called “Why I’m Disappointed in Jesus.”