By Akin Ogunlade

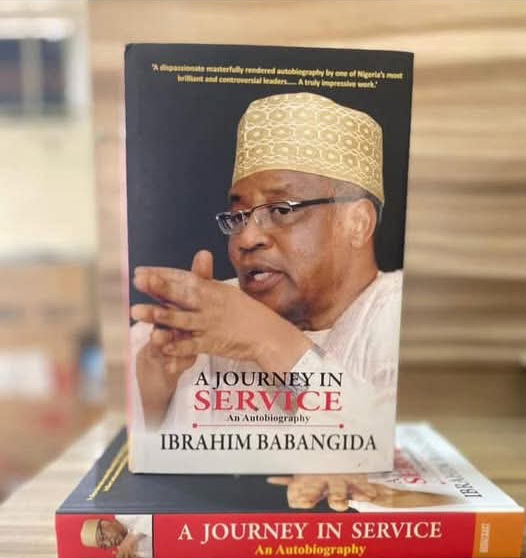

The recent launch of former military ruler Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida’s memoir, A Journey in Service, has once again sparked conversations about Nigeria’s political history, particularly the scars left by the annulment of the June 12, 1993 election. For many Nigerians, Babangida’s attempt to recast his legacy in a more favorable light feels like an appeal to the wounded souls still grappling with the consequences of that fateful decision. It also raises a pertinent question: do Nigerians suffer from collective amnesia when it comes to their political past?

The wound of June 12

The annulment of the June 12 election, widely regarded as Nigeria’s freest and fairest poll, is one of the darkest stains on the nation’s democratic journey. The presumed winner, Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola, was denied his mandate, leading to years of political instability, protests, and ultimately his tragic demise while in detention. The annulment shattered trust in the electoral process and deepened Nigeria’s struggle for democratic credibility.

Despite these painful memories, Babangida has continued to enjoy a degree of political rehabilitation. His book, instead of offering a sincere reckoning with the past, appears to be an exercise in self-vindication. The question is: why do Nigerians allow figures who presided over national tragedies to rehabilitate their images so easily?

A Nation that forgets too soon

Nigeria’s political landscape is riddled with instances where past leaders, despite their controversial legacies, find ways to return to the public space with little to no accountability. The cycle of historical revisionism is made easier by a populace that, either due to disillusionment, survival instincts, or the passage of time, fails to demand sustained justice or acknowledgment of wrongdoing.

This pattern is not unique to Babangida. Many former leaders accused of misgovernance, corruption, and repression have found their way back into relevance, often rebranding themselves as elder statesmen. The lack of institutional memory, partly due to weak historical documentation and an educational system that downplays civic awareness, makes it easy for new generations to remain disconnected from the past.

Selective outrage and political convenience

It is worth noting that outrage in Nigeria often flares up in the heat of the moment but rarely translates into long-term consequences. Public anger over political betrayals, electoral malpractices, and human rights violations tend to dissipate quickly. Moreover, political elites have mastered the art of manipulating narratives, using media influence and strategic alliances to reshape public perception over time.

Babangida’s memoir is a case in point. While some Nigerians still harbor resentment over his role in annulling June 12, others, either out of nostalgia, political alignment, or sheer pragmatism, are willing to listen to his version of history. This dichotomy reflects a deeper societal challenge: the inability to sustain collective memory as a tool for accountability.

The danger of forgetting

The failure to remember and hold leaders accountable has dire consequences. It allows the cycle of impunity to continue, with new generations of politicians repeating the same mistakes or worse. A nation that forgets too soon is bound to relive its worst moments.

As Babangida attempts to frame his years in power as a “journey in service,” Nigerians must ask themselves: service to whom? If the service was to the nation, why does his legacy remain marred by unfulfilled promises, unhealed wounds, and unresolved questions?

Rather than allowing historical revisionism to take root, Nigeria must strengthen its culture of historical awareness. This includes institutionalizing civic education, encouraging investigative journalism, and ensuring that public records remain accessible for future scrutiny. Only then can the country break free from the cycle of collective amnesia and move towards genuine national accountability.

The past should not be rewritten to suit those who shaped it; it must be remembered so that future generations can learn, demand better, and ensure history does not repeat itself.