To participate in the process without addressing its structural infirmities is to confer a veneer of legitimacy upon a charade.

When news broke that Peter Obi had joined pro-democracy activists and youth groups in a protest at the National Assembly under the banner “Occupy the National Assembly,” I was compelled to read and reread the report. This was not the political temperament Nigerians have come to associate with the former Labour Party presidential candidate. Obi is measured to a fault, deliberate almost to the point of excessive restraint. For such a man to march in Abuja, at personal risk of being tear-gassed by the regime’s security forces, suggested matters of existential significance.

The immediate catalyst was the passage of the Electoral Act 2022 Repeal and Re enactment Amendment Bill, 2026. In revising Nigeria’s principal electoral statute ahead of the 2027 general elections, the Senate excised the phrase “real time” from the clause concerning electronic transmission of results. The consequence is subtle in wording yet profound in implication. The law no longer unequivocally mandates that results from polling units be uploaded instantaneously to INEC’s central portal upon announcement. Instead, the timing and modality of transmission of results, are left substantially to the discretion of the sweet men and women of Nigeria’s not-so-Indipendent INEC.

To the uninitiated, this may appear an arcane legislative adjustment. In a polity burdened by a history of opaque collation processes and nocturnal electoral alchemy, however, the distinction between immediate transmission and discretionary transmission is not trivial. It is the difference between transparency and plausible deniability.

Nigeria now stands on the cusp of another four yearly ritual dignified by the name general election. Candidates will be unveiled. Rallies will be convened. Political newbies will be led to swear the oath of allegiance before a dreaded deity and the incumbent made to dine with the devil to guarantee a return ticket. Yet beneath the choreography, a more disquieting possibility looms. For the first time in Nigeria’s history, the presidential contest threatens to resemble an elite adoption exercise. The days of pretending that citizens have power to effect an electoral outcome is over. The job of the electorate is simply to ratify what has already been tacitly resolved within the inner sanctums of power.

The Nigerian elite, under the firm grip of Asiwaju Tinubu, a man who has time and again proven himself one of the most ardent disciples of Niccolò Machiavelli south of the Sahara, appears to have it all figured out. If you are a governor seeking a second term, you know precisely what is required of you. Alternatively, you may choose to be an Alex Otti and believe that your stellar record will render any attempt by the selectorate to unseat you politically untenable. Time will tell. But the message from the President’s camp is pretty clear; Loyalty is rewarded. Defiance is neutralized. Ambiguity is eliminated.

Once upon a time, state governors, fortified by constitutional autonomy and their commanding influence over party structures within their domains, exercised decisive leverage in determining who ascended to Nigeria’s presidency. Their collective weight often proved determinative in the calculus of national power.

President Tinubu’s own emergence in 2023 bore testimony to this enduring dynamic. A cohort of northern governors asserted themselves against elements within President Buhari’s inner circle, many of whom were implacably opposed to Tinubu’s candidacy. Without that intervention, the late president’s loyalists, armed with the full apparatus of incumbency and institutional influence, would in all probability have dictated a different outcome.

But times have changed. Machiavelli’s Prince has studied these power dynamics closely and resolved to curtail them. He signaled what the new order would look like in the political neutralization of Nasir El Rufai who, though I am no admirer of his politics, was arguably the most prominent among the northern governors who played a decisive role in Tinubu’s emergence. Like a calculating prince, the president appeared to conclude that the diminutive and often mischievous figure could not be sufficiently trusted with a role not explicitly defined in the script.

He then followed by firing what was clearly intended as a warning shot, designed to leave no ambiguity even for the doubting Thomases, when Governor Fubara, then viewed as recalcitrant, was unceremoniously suspended for six months. The National Assembly swiftly gave its blessing, and the judiciary seemed already aligned with the logic that decisive action, once taken, would be judicially accommodated. The requisite validation appeared assured even before the intentions were publicly crystallized.

No one mounted any meaningful resistance. No sustained alarm was raised about a constitutional crisis. It was as though those who once cautioned President Jonathan against even contemplating such measures had disappeared from the public square. In the end though, Mr. Fubara shed his prodigal son persona and emerged as the model good boy, executing the script with dutiful precision, just as the Prince like it.

In such a climate, what does opposition politics even mean today in Nigeria, when the institutional ecosystem appears harmonized in favor of incumbency? Do the so-called opposition parties truly believe they are contesting in 2027? Do Atiku, Obi, or Kwankwaso genuinely think they stand a chance? Or are they merely actors in a carefully choreographed spectacle of managed competition, its parameters predetermined and its outcomes tacitly circumscribed?

The garb remains civilian. The rhetoric remains democratic. But the operation increasingly feels choreographed with military precision. Yet the choreography increasingly resembles governance by a selectorate rather than by a sovereign populace. The President wields power in a manner that would have made Mobutu green with envy. We profess adherence to the American presidential model, having once experimented with Westminster parliamentarianism. In practice, however, we appear to have evolved a bespoke system in which elite consensus circumscribes popular choice.

The problem with opposition politics in Nigeria is that few, if any, among its leaders value the arduous struggle required to contest power over the comforts of personal freedom. These are no warriors forged in the treacherous mountains of Tora Bora or the merciless jungles of the Amazon rainforest. Rather, they are corporate elites who, until now, have lived in gilded mansions and traversed the globe in luxury Bombardier jets. They are enamored with the allure of power when it is handed to them on a platter, yet they are seldom prepared to seize it through sustained and ruthless effort.

In the aftermath of the 2023 presidential election, I engaged one of Peter Obi’s prominent allies in a public exchange. My question was straightforward: why should Nigerians reinvest their hopes in a candidacy that, even if victorious, seems hesitant to mount a robust defense of its mandate? I cited instances in which Labour Party victories at subnational levels were either overturned or diluted. The response was that Obi was mindful of a ruling establishment ready to exploit any provocation as a pretext to put him away for good.

Such caution is not irrational. Politics is a game of cat and mouse, after all, yet history delivers a stern admonition: an elite of rent-seekers will not relinquish power out of the abundance of their goodwill. History teaches us that those who pursue transformational politics do not fold like a cheap skirt in the face of threats. They are prepared to endure a bloodied nose if necessary. If one is unwilling to endure the furnace of political contestation, one should reconsider entering the arena.

In an earlier essay titled “Beyond Peter Obi: A Hero for a New Era,” I acknowledged Obi’s catalytic role in reawakening political consciousness among a generation disenchanted with the status quo. His campaign galvanized an organic movement that disrupted entrenched assumptions. Nevertheless, inspiration alone cannot achieve the task. A Moses may lead a people out of Egypt, but a Joshua must possess the resolve to breach the fortified walls required to reach the Promised Land.

Obi’s decision to protest the amendment of the electoral law therefore signifies both growth and urgency. It reflects recognition that incremental erosions of procedural safeguards accumulate into structural disadvantages. Yet symbolism, however commendable, cannot substitute for sustained strategy.

Had the opposition collectively demonstrated from the outset a coordinated and relentless commitment to defending electoral integrity, the present aura of inevitability surrounding 2027 might not have solidified. When controversial 2023 election results were announced in the dead of the night, the response was predominantly juridical and rhetorically restrained. Petitions were filed. Press conferences were held. The streets, however, remained largely tranquil.

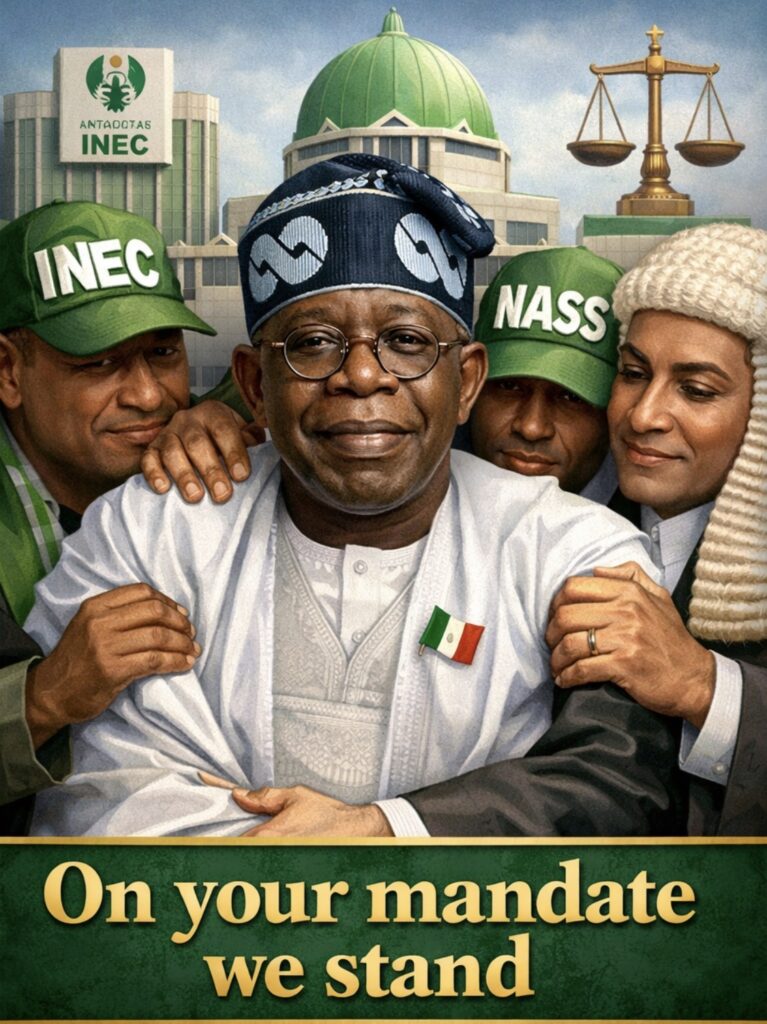

A political establishment that perceives no existential peril from its adversaries is disinclined to concede ground. A National Assembly that uses every opportunity to sing “on your mandate we stand” with near liturgical fervor, will seldom impede its legislative preferences. A judiciary whose interpretive latitude has expanded in politically sensitive matters commands both authority and controversy. Within such a configuration, what is the opposition’s endgame?

Can it plausibly arrest a locomotive already accelerating toward its predetermined terminus? Or does its participation risk conferring democratic legitimacy upon an outcome that may already be inscribed?

Fear is a human constant. Many Nigerians, fatigued by economic precarity and institutional volatility, prefer stability to confrontation. This is understandable. What is less defensible is the simulation of resistance while tacitly legitimizing a process one privately regards as compromised.

If 2027 is to transcend ritual and embody authentic contestation, reforms must be unequivocal. Electoral transmission protocols must be explicit rather than discretionary. Opposition parties must subordinate personal ambition to strategic coherence. Civil society must sustain vigilance beyond episodic outrage. Above all, citizens must be persuaded that their ballots traverse a transparent pathway from polling unit to final declaration.

The excision of two words from a statute may appear inconsequential. In fragile democracies, however, textual nuance often signals political trajectory. Real time transmission is not a technological indulgence. It is a prophylactic against the opacity in which manipulation flourishes.

Peter Obi’s march to the National Assembly may prove a harbinger of more assertive engagement, or it may recede into the annals of symbolic dissent. The determinant will be what follows. Will there be sustained mobilization within constitutional confines? Will alliances coalesce around procedural integrity rather than personal aspiration? Will Nigerians demand not merely the performance of democracy but its substance?

As the nation approaches 2027, a credible opposition must be unequivocal in its stance. It demands an answer to a vexing question: are we preparing for a genuine election, or merely rehearsing the aesthetics of one? To participate in the latter without addressing its structural infirmities is to confer a veneer of legitimacy upon a charade, wholly unworthy of citizen participation.

Osmund Agbo is a medical doctor and author. His works include Black Grit, White Knuckles: The Philosophy of Black Renaissance and the fiction title The Velvet Court: Courtesan Chronicles. His latest works, Pray, Let the Shaman Die and Ma’am, I Do Not Come to You for Love, have just been released. He can be reached at eagleosmund@yahoo.com.