By Chidi Anselm Odinkalu

If you wanna live – treat me good

If you wanna live, live –

I beg you treat me good

I’m like a walking razor

Don’t you watch my size

I’m dangerous, said I’m dangerous

I’m like a walking razor

Don’t you watch my size

I’m dangerous, dangerous.

Peter Tosh, Steppin’ Razor (1977)

Winston Hubert McIntosh, the Jamaican martial arts exponent better known by his stage name Peter Tosh, was one of the trio – together with Robert Nesta (Bob) Marley, and Neville Livingstone (Bunny Wailer) – who founded the legendary Reggae band, the Wailers, in 1963. By 1974, the group was all but dissipated. First Bob Marley and then Peter Tosh launched off into what would become epochal solo careers.

Their respective paths as solo artistes telegraphed the ideological conflicts that ultimately sundered the Wailers. While Bob Marley’s music offered a medley of reconciliation, romance, and regroup, Peter Tosh was muscular in protesting the injustices of his environment. His solo debut in 1976, which came out under the title “Legalize it,” was way ahead of its time in making the political and clinical case for the legalization of Marijuana.

The following year, in 1977, Peter Tosh’s second album which came out under the title “Equal Rights,” was to become the anthem of an international movement for social justice whose birth coincided with the launch of the album. One of the tracks in this album was “Steppin’ Razor,” a perspicacious dirge of self-assertion which was to define his identity in life as well as his legacy upon his untimely killing ten years later in 1987.

Musicians, of course, have an entitlement to artistic license in framing themselves in public imagination, which is not necessarily available to other vocations. Forsaking the rules that control their own vocation, it now seems that some judges in Nigeria may prefer, like Peter Tosh, to exercise both artistic license and faux testicularity in inventing themselves in judicial fashion as Mr. Justice Steppin’ Razor.

In August 2023, for instance, Flora Azinge, a senior judge of the High Court of Delta State presiding over election petitions in Kano, north-west Nigeria, complained publicly for the second time in open court that “a senior member of the bar offered one of her staff a sum of N10 million bribes for onward delivery to the panel.” On an earlier occasion, she has claimed that an un-named senior lawyer had asked her to provide him with her account for the transmission of a seasonal gift.

Preferring instead to flex her credentials as Madam Justice Steppin’ Razor, the judge was reported as having threatened that she “would no longer take any attempt to bribe judges, saying that attempts to pervert the cause of justice through the back door is not tenable in her court.” She did not say what she would be prepared to do or how many importunations it would take for her to do them.

In the court hall where the judge voiced these claims, there were lawyers present but none had the courage or presence of mind to remind her that she had powers to deal summarily with the complaints that she raised or that by choosing not to exercise those and instead bury them in anonymous allegations, she was actively involved in bringing her judicial office into disrepute.

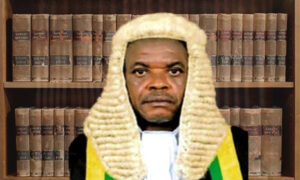

This past week, Emeka Nwite, a judge sitting in Abuja, has chosen to join the ranks of the judicial Steppin’ Razor, in announcing that he is “dangerous.” The occasion was the adjourned sitting of the Federal High Court in the Federal Capital Territory for the hearing of the application for bail in the trial of former Attorney-General of the Federation, Abubakar Malami, his wife, and his son on charges of money laundering and aggravated pillage of Nigeria’s patrimony.

After granting the application of the accused for bail, the judge is reported to have launched into what can at best be described as performance-enhanced monologue, suggesting that he had been importuned by some senior lawyers to compromise the case or to “go easy” on the accused: “When I am handling any case, please don’t approach me. When you are doing your case, you can get the best lawyers in this country to do your case, but don’t attempt to approach me for any help. I am not the type of judge. I know what God has done for me by giving me this job, and I have vowed to do it to the best of my ability. I have sworn before Almighty God and man that I am going to do my duty without fear or favour.” He added, with a touch of hyper-ventilation, that “any attempt to try this will be vehemently resisted.”

His audition for the position of Mr. Justice Steppin’ Razor this time was a tad more pathetic than the earlier example. In one stroke the judge undermined his claim that he is not the type of judge who can be influenced and made his promise of vehement resistance to such sound desperately shameful.

To understand why, it is relevant to recall that Nigeria’s Constitution makes it a human right that all courts must be “independent and impartial.” The Judicial Code of Conduct requires all judges to “preserve transparently, the integrity and respect for the independence of the Judiciary.” According to the United Nations Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, judges “shall decide matters before them impartially, on the basis of facts and in accordance with the law, without any restrictions, improper influences, inducements, pressures, threats or interferences, direct or indirect, from any quarter or for any reason.”

It amounts to a perversion of the cause of justice to seek to influence a judge in the performance of his or her judicial functions. There are many options for dealing with this. One, the affected judge can report the matter to the police or to the Attorney-General for investigation and prosecution. Two, the affected judge is also endowed with powers to punish it summarily as an act of criminal contempt for which the guilty person may be sent to jail. Three, if the perpetrator is a lawyer, a public servant, or other regulated professional the judge may additionally refer the conduct for disciplinary process before mechanisms of professional sanction. Four, the judge could use his or her judicial bully pulpit for naming and shaming by inviting the perpetrator to allocute to or admit the facts in open court and simply reprimand thereafter.

Our latest Mr. Justice Steppin’ Razor is so endowed with courage that he managed in this case to not consider any of these options worthy of his exertions. Instead, he bloviated, threatened, auditioned for the role of Steppin’ Razor, and was so dissipated by the colossal effort required for all these that he could not even manage to name the person or persons to whom his threat or resistance was addressed.

On the whole, this shameful show was a squalid advertisement of judicial malpractice. A judge who finds himself or herself in a position to make the kind of public declamations that our latest Mr. Justice Steppin’ Razor made in court has two options: to disclose the identity of the perpetrators and subject them to sanction or to recuse himself or herself from further participation in the case.

In this present case concerning Malami et fils, the judge was unwilling or unable to muster either. Instead, he chose to threaten consequences for a future contingency whose occurrence, on the evidence of the current one, we are unlikely to ever hear of. The only thing the judge managed to accomplish in this case, therefore, was to publicly advertise his availability to be nobbled. Peter Tosh, the original Mr. Steppin’ Razor, will suffer no fear that his title is about to be taken away. The most recent judicial candidate failed the audition hopelessly; it was not even close.

A lawyer and a teacher, Odinkalu can be reached at chidi.odinkalu@tufts.edu